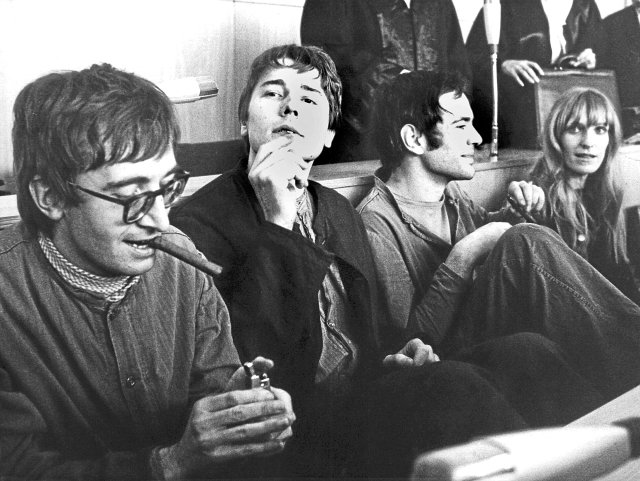

Does not seem uninhibited: Andreas Baader in court in Frankfurt/Main 1968 (3rd VL, in a row with Thorwald Proll, Horst Söhnlein and Gudrun Ensslin).

Photo: Manfred Reh/dpa

Can you feel free in prison? Andreas Baader somehow, you believe his biographer Alex Aßmann. The co -founder of the RAF only felt “free in prison”, according to the title of Aßmanns in the spring of the book, which was published alongside Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin, the best -known figure of the so -called city guerrilla, which dissolved in 1998. “I’m a poet. I live a novel, «is the first sentence in the book. A quote from Baader, which shows its political and personal will to design as a prisoner, long before Stuttgart-Stammheim.

It comes from his prison diaries, which he wrote when he was in custody for a little more than a year in Frankfurt am Main and was waiting for his process. At the beginning of April 1968, Ensslin, Horst Söhnlein and Thorwald Proll had fired fires in two Frankfurt department stores to protest against the Vietnam War. Nobody was harmed. They were revealed and arrested just two days later. Baader only became clear in prison what that was supposed to do.

How do you become a revolutionary? In custody he fully wrote eleven claddes and notebooks, which Aßmann has historically evaluated for the first time. This results in a different view of Baader than the one that is otherwise offered to you in the media, especially by the journalist and RAF chief explanator Stefan Aust.

In feature films such as “The Baader-Meinhof complex” (2008) and “Stammheim-Zeit der Terror” (2025), in which Aust was involved, Baader appears as a screaming with the urge to Macker and asshole. If the script says it a little better with him, he gets a hint of Jean-Paul Belmondo in “Out of breath”, but still has to roar around a lot, as in “Baader” (2002), to which Moritz of Uslar wrote the script.

In the presentation of Alex Asßmann, on the other hand, Baader appears as a thoughtful young man who wants to determine his image himself – in the consciousness, by the department store and the upcoming process in public. In order to be able to raise political demands, he must first become clear about the society in which he lives. This happens through the books he reads in jail (Marcuse, Lenin, Fanon, Flaubert and Wittgenstein again and again), and about the letters he writes from jail, above all to his loved one. With her he discusses his inner conditions, his reading and also the relationship with his mother. They also develop an eroticism of the locked up by exchange ideas about the novel “Justine” that Marquis de Sade wrote when he was also caught.

The special thing about Baader’s letters: they look casual and concise, as associative, but they are the result of several designs that Aßmann could see in Baader’s notebooks. Sometimes Baader has to try six variants until he can send a letter that finally sounds as he imagines it: not too lyrical, not too artificial, but as if he had not written it, but spoke. “In order to act in the text as was known in the oral conversation, he had to compose cleanly, but wrote incorrect letters,” explains Aßmann, who assumes that Baader has partially declamated his letters in the cell to check their effect. A great effort for apparently spontaneous gestures.

For Baader, this writing was of existential importance, since he wrote against the depression that came over in custody. By reading and writing, according to Aßmann, he created a kind of double with literary means that he could freely dispose of, or as Baader puts it in his diary: “I sat on Wittgenstein like a horse how to sit on it and thus sit over the wall.”

He was arrested in Frankfurt two days before his 25th birthday. At that time he didn’t succeed too much in his life. He had flown from the high school in Munich, had not made it at a private school and could not meet his mother’s demands – a widow of war whose brother worked as an actor and was looking for the connection to so -called artists. Baader was a loner who noticed through thefts, driving without a driver’s license and fights, not through political ambitions; Even when he moved to West Berlin, with the artist couple Ellinor Michel and Manfred Henkel lived together and became a marginal figure in the municipality 1. With Michel, he put daughter Suse into the world, which Henkel had to take care of. Although this history makes up half of Aßmann’s book, Baader remains indistinct as a figure, as if the author wanted to emphasize that Baader did not really know what he wanted for a long time.

On the other hand, he appears very productive as a prisoner, writing letters and diaries looks like an “practice in itself and through himself,” as Aßmann Michel Foucault quotes. It is always about the social framework. For Baader, Western capitalism is violent and manipulative. He believes that the protest, on the other hand, should also be violent in order not to be talked out and ultimately integrated: »For us, violence is the only chance for us to be grinded in this society. The only chance to show (…) that you have to talk to us and not with a few reforms that can stuff the mouth. “Baader is certain:” The rulers only react to violence. “

Baader develops such positions in designs for his own appearance in court. At the same time, he writes on a screenplay for a feature film about the department store fire, which his acquaintance, the young director Klaus Lemke is supposed to shoot as a “vision from below”. At the same time, authors from the environment of the alternative magazine “Charlie Bruss” would like to have texts for a anthology about the left -wing radical West Berlin scene. Agitation in court, in film and book: For Aßmann, Baader is the “curator of a complex multimedia project” with the aim of “driving the protest to the utmost,” as Baader put it.

However, his big appearance in court fails, Klaus Lemke is making the film “arsonist” differently than by Baader, and the anthlete published by Hartmut Sander “Subculture Berlin”, including letters from Baader, Ensslin and Proll, he was also not good.

In contrast to other revolutionary young politicians who will soon start to found groups in a pathetic way that they want to sell as new forms of proletarian parties, Baader is aware that the workers cannot be achieved “because they are chained by the mass media and their manipulated needs”. Instead, it should be clarified “that bourgeois existence fails to us”.

He stands on the other side of bourgeois society and believes: “You are free in the cell, so to speak.” A deduction on its own behalf, formulates like a proof of God. He said to the court that he did not want to acknowledge: “The person Baader no longer exists (…) I can tell you something about the captured baader.” He no longer gave up this status, even if the RAF was founded in 1970 by the liberation of Andreas Baader. That was first experiment, then bloody disaster.

In 1972 Baader was arrested again, this time as an enemy of the state number 1, and then he died in 1977 in the prison of Stuttgart-Stammheim, very likely through suicide. Is that particularly morbid irony, or was he an anti -state existentialist? The fact that you can think about the paradoxes in his life is a great performance by Alex Aßmann.

Alex Aßmann: Free in prison. Andreas Baader, the arsonist process and political violence. Edition Nautilus, 288 pages, Br., € 22.