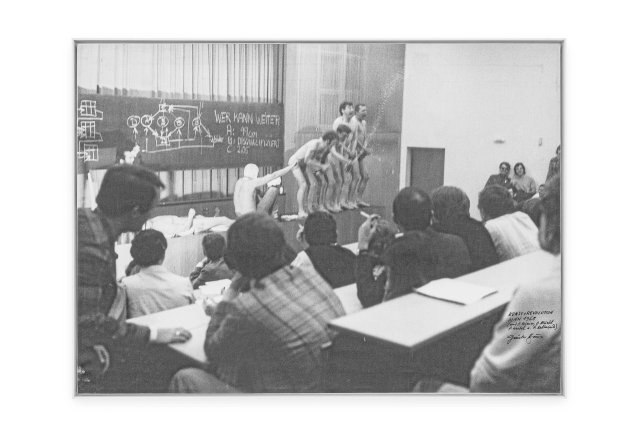

Would probably not leave you indifferent today either: the “Art and Revolution” campaign, in which four artists, among other things, relieved themselves naked, injured themselves and masturbated while singing the Austrian national anthem in a lecture hall at the University of Vienna

Photo: Manuel Carreon Lopez

Why is the Vienna Actionism Museum (WAM) needed?

Viennese Actionism is Austria’s most important art movement after the Second World War and one of the most important contributions to avant-garde art of the 1960s and 1970s as a whole. Internationally, various action art forms such as performance, happenings and Fluxus emerged during this time – in this context, Viennese actionism emerged as a very special, physically radical art movement that set standards for everything that followed. That’s why Vienna definitely needs a place where Viennese activism is permanently contextualized.

So why did WAM only open in March of this year?

For a long time, the Museum of Modern Art (mumok) in Vienna was relied upon as an international center of excellence for Viennese Actionism. In addition, Viennese activism is always politically charged, and how much visibility it is given depends largely on the cultural-political situation. Conservative forces did not want such an extreme avant-garde movement to over-represent the city.

Interview

©Studiokoekart

Julia Moebus-Puck is an art historian and in 2023 was entrusted with the management of the Vienna Actionism Museum (WAM), which opened in March 2024. She previously worked as an art educator for, among others, the Max Ernst Museum in Brühl, the Arp Museum Bahnhof Rolandseck, Art Basel and the Albertina Museum Vienna. From 2020 to 2022 she built up the exhibition archive of Richard Long, the main representative of Land Art.

But politics didn’t have that much to do with the WAM, since it is a private institution.

That’s right, the museum is a private initiative of six collectors who bought up the remaining holdings of the Friedrichshof Collection when it was dissolved – which was the most extensive collection of works by the Actionists up to that point. The buyers were so aware of the art historical significance of these works that they really wanted to contextualize them together in a museum – that’s how the WAM came about.

The Viennese Actionists were four men: Otto Muehl, Hermann Nitsch, Rudolf Schwarzkogler and Günter Brus. They made art with their own bodies, but also with those of women. Actions in which women allowed themselves to be tied up naked or otherwise “processed” by them and then displayed to an audience do not seem particularly feminist today.

Last week I gave a tour where a younger woman was quite shocked by some of the photographs. “Everywhere in these photos there are men standing around a naked female body,” she said. I myself have actually never viewed the actions from the perspective of gender roles – but the more often I am confronted with such observations, the more clearly I see this aspect. But I think it is very important to point out that these situations were definitely ambivalent. If, for example, Ana Brus – who was often involved as Günter Brus’ wife – now says that some actions were almost emancipatory acts for her, then we have to take that into account.

To what extent could such depictions of naked women’s bodies have been emancipatory acts?

Of course it depends on the context, but today showing naked female bodies is no longer associated with liberation. At the time of the Sexual Revolution, things were different: naked bodies were a taboo violation. In addition, such an action was not intended to confirm reality, but rather was a provocation. The artists perhaps also wanted to criticize certain role models by exaggerating them.

Viennese actionism often seems quite brutal and bloodthirsty. I’m thinking, for example, of the “Blood Organ” campaign, in which a dead lamb was crucified, disemboweled and torn to pieces. What was progressive about it?

The artists have radically addressed actions or physical processes such as vomiting, masturbation, urination, defecation as well as the associated bodily excretions and blood. They were of the opinion that these taboo topics are part of human beings and need to be presented in this way so that something can change in society. The actions with the animal carcasses also have this critical aspect of civilization. Animal sacrifices are central elements of the most diverse cultures around the world; they are part of the origins of our civilization.

It seems as if the artists wanted to go back to the archaic – but is that the solution? Shouldn’t it be more about building a different, better civilization rather than rejecting civilization as a whole?

In any case, it was about creating a civilization different from that of the time. The Viennese Actionists thought that if you go back to this originality, you will create a new consciousness. When I lead young people through Hermann Nitsch’s exhibition, they often find the handling of animal carcasses totally disgusting – but when I then ask them whether they eat the prepackaged minced meat from Billa (Austrian supermarket chain, editor’s note), They realize that animals also died for this. In order to raise awareness of such connections, it might not hurt to go back to the archaic.

Viennese Actionism is repeatedly associated with Sigmund Freud and the psychoanalysis he founded. What connecting points are there?

Incredibly many. All modern art refers to psychoanalysis in many different ways. All Viennese modern artists – Oskar Kokoschka, Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele – were influenced by Freud’s insights. They were all very interested in how the body and mind are connected. And if you look at the “action sketches” by Günter Brus in our museum, for example, it becomes clear how much this work with the battered, defragmented body was influenced by Schiele. The actionists continued the form of physical work and thinking in Viennese modernism by bringing what they saw on paper or canvas into space. Another point of reference to Freud is that all actionists attributed a cathartic effect to their art. When, for example, Muehl and Nitsch threw paint onto the canvas and rolled around in it, they understood this as a process of acting out through which unconscious drives came to light and led to a new experience of being.

Performance art is, by its very nature, fleeting. Unlike paintings or sculptures, it can only be exhibited through media. How do you approach this in your museum?

During their lifetime, the actionists were already concerned with how they could document and process their ephemeral actions. This means that they have had their work photographed or filmed right from the start. There were two different approaches to photographic documentation: on the one hand, the classic photographing of action sequences, and on the other hand, staged photography, which all actionists practiced between 1964 and 1966. Actions were not carried out for the public at all, but only for photos. Likewise, the artists’ paintings and drawings, which were repeatedly created during their actionist activities, are a type of documentation. Hermann Nitsch also created so-called relic collages. And then there are scores: every action was recorded in advance in a score, so they were by no means improvised events. As a curator, you have to think about what exactly you want to tell with an exhibition, and that can require very different means. So you have to keep thinking about which form of presentation is the most suitable.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola online judi bola judi bola judi bola