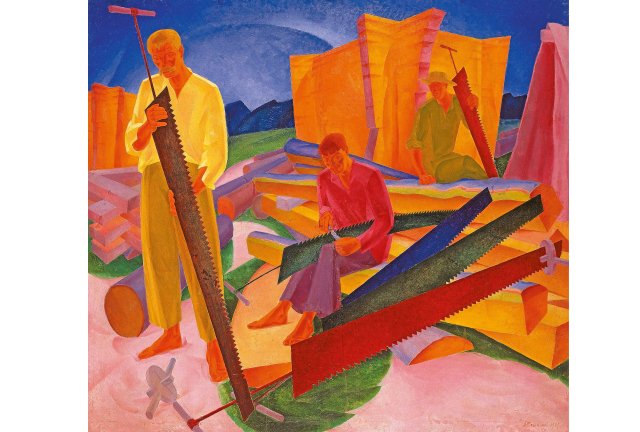

Building a new society: Oleksandr Bohomazov, “Sharpening the Saws” (1927)

Photo: National Art Museum of Ukraine, Kyiv

A sketch by Kasymyr Malevych. El Lissitzky’s geometric figures. And there further ahead is a formidable example of Alexandra Exter’s cubo-futurism…

A hall filled with the best works by avant-garde artists who worked in Ukraine opens up to visitors to the Belvedere Museum in Vienna. The invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops in 2022 and the long tradition of Russian imperialism against the country haunt the works everywhere.

The Russian war of aggression also plays a very specific role in the design of the exhibition entitled “In the Eye of the Storm – Modernisms in Ukraine”. The art treasures hanging on the walls were rescued from Kiev by local museum staff and drivers during a hail of bombs. According to curator Katia Denysova, it happened like this: “Unfortunately, we chose November 15, 2022 to transport the valuable cargo – a day when one of the most serious attacks took place and the Russian military fired hundreds of rockets into Ukrainian cities. They hit everywhere as the trucks set off, making the journey extremely nerve-wracking for everyone involved. To escort the paintings through the war-torn country, President Volodymyr Zelensky personally provided a military convoy.”

On display in the exhibition, for example, is Oleksandr Bohomazov’s “Sharpening the Saws” from 1927. The painting addresses the attempt to build a new society – with the founding of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic in 1919 and the efforts to introduce socialism. As one of the central works of the exhibition, the work is stunning in its composition and its bright yellow, blue and purple shades.

The War calls for a fresh look at Bohomazov’s masterpiece and the remaining legacy of the artistic avant-garde of the 1920s. The ideas and work of the movement were long considered the pinnacle of Russian art. Now Denysova and other art historians emphasize that many of the artists actually came from Ukraine and worked there. Like Kasymyr Malevych – the creator of the “Black Square” – they were often inspired by traditional Ukrainian folk art and spoke Ukrainian. There is now a tendency to move away from the Russophile and colonialist view of the region’s avant-garde art, which the West has so far uncritically adopted, says Denysova.

“For a long time it seemed convenient to simply label this kind of art as Russian, rather than trying to understand the jumble of national identities that made up the Russian Empire or the Soviet Union or exist in the Russian Federation today,” she says.

The one-sided focus on the Russian imperial center when it comes to avant-garde art says a lot about the mindset of Western European museum directors, art historians and curators and the largely unresolved colonial legacy in their own cultures. The exhibition and the associated attention have ensured that museums with renowned collections of avant-garde art, such as the Stedelijk in Amsterdam, the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the Ludwig in Cologne, are now finally starting to correct inaccuracies.

The title of the exhibition, in German »“In the Eye of the Storm” refers to the dramatic historical situation at the time, characterized by the collapse of empires, the First World War, revolutions and the founding of the Ukrainian Soviet Republic. At that time, the Ukrainian avant-garde was sprouting in cities such as Odessa, Kiev and, above all, Kharkiv. Among other things, artists tried to find a modern formal language for a new national identity. Long oppressed by the Russian Empire, they sought expressions that suited Ukrainian self-determination.

The overall picture was colorful. The identities were fluid. A multitude of artistic movements followed one another. Just as the term “avant-garde” itself encompasses a variety of “isms” such as constructivism, cubofuturism, suprematism or boychukism, there was a fascinating mix of sources of inspiration and views among the artists.

This Ukrainian avant-garde was not given long time to develop. In order to suppress any potential opposition to the Soviet project – now in its Stalinist version – the regime used massive repression.

»They culminated in 1937 and 1938 during the so-called Great Terror. In Ukraine this means, among other things, that a generation of the most talented artists – often at the peak of their careers – were executed or perished in Siberian prison camps, blamed for ›civil nationalists‹ to be. Their works were taken to secret depots or destroyed«so Denysova.

The repression reached such a level that the Ukrainian artists of that time are simply referred to as “the executed Renaissance.” Her murder and the destruction of her works parallel the current systematic attempt by the Russian armed forces to destroy Ukrainian cultural heritage such as museums, libraries and historical monuments.

Denysova looks with admiration on the local museum employees in Kiev who rescued the exhibition’s works from the inferno and thus made them accessible to the Western European audience. »Before works of art go into an exhibition, they are often restored. Paints and canvases are being touched up. Some need new frames. They need to be packaged safely for transportation and so on. All of these tasks were carried out by our colleagues under heavy Russian attacks, in an everyday life of air raid alarms, sounds of explosions, curfews and power outages. They often had to spend the night in the museum and then work when there was electricity. Through these efforts, a long-overlooked chapter in European art history can now be opened.

“In the Eye of the Storm – Modernisms in Ukraine” has already been shown in Madrid, London and Brussels. Until June 2nd at the Belvedere Museum, Vienna, then from June 29th to October 13th at the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!