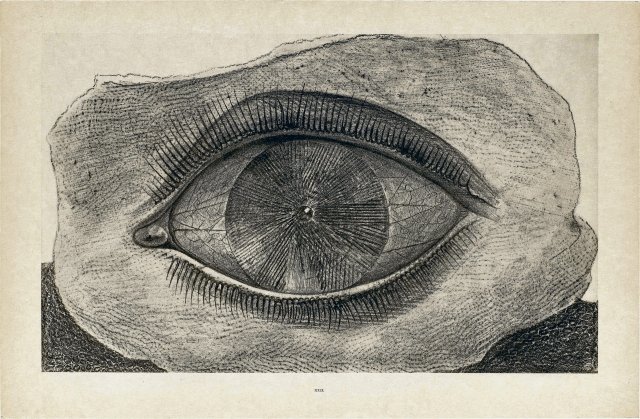

Max Ernst took dreaming seriously. A drawing from the “Histoire naturelle” cycle, created in 1925

Photo: Archiv der Avantgarden – Egidio Marzona, SKD, Photo: Elke Estel

It has now been eight years since the tranquil art world in the Saxon capital experienced a bang: The Italian patron and art collector Egidio Marzona announced at the time that the “Archive of the Avant-Gardes” – ADA for short – that he had compiled over many decades would be in perspective would be transferred to the property of the Dresden State Art Collections (SKD).

The award came as something of a surprise at the time: just two years earlier, Marzona had publicly announced that the ADA would probably go to Berlin. The Cultural Forum at Potsdamer Platz was considered a hot contender at the time. The decisive reason for Dresden, it can be assumed, was the fact that the then newly appointed general director of the SKD, Marion Ackermann, promised Marzona her own house for the archive.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

That’s how it happened: After a fundamental renovation that began in 2017 and lasted a total of six years, the collection of the now 80-year-old Marzona was recently transferred to the Dresden Blockhaus. An initially idiosyncratic choice – its baroque facade in the immediate vicinity of the Augustus Bridge and the Golden Rider symbolizes the exact opposite of what the archive’s predominantly radical artistic products stand for. In any case, Dresden, with its traditionally courtly character, had not distinguished itself as a city of the avant-garde in the past. This could now at least partially change with the newly acquired archive.

The ADA includes a total of 1.5 million objects from the 20th century. Marzona, whose father owned a concrete factory, comes from a wealthy German-Italian family. His family background gave him the freedom and certainly the necessary change to collect his first objects from the world of the avant-garde when he was in his mid-20s. In addition to the works of art themselves, he was particularly interested in the conditions under which they were created.

He collected correspondence, photos, books, designs, furniture, design objects and much more. What began as an undirected hobby became increasingly systematized over the years, including global networking and research. He accepted the obvious contradiction of providing a radically future-oriented art movement with archival demands without resolving it.

300 of the ADA objects are now in a first exhibition called “Archive of Dreams. A Surrealist Impulse”. The focus on surrealism was obvious, as the “Surrealist Manifesto” by the French writer and art critic André Breton, which was fundamental to its history, celebrated its 100th anniversary this year. The most prominent representative of the movement to date is the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí, whose portrait with an iconographic beard also adorns the exhibition poster. Dalí was anything but uncontroversial within the movement: as early as 1934, he was excluded from the core group around Breton due to his refusal to take part in left-wing political activities – although he continued to exhibit his works with the artist group for five more years.

The core of the exhibition project – as the catalog says – is the realization that “dreams represent an essential phenomenon if one wants to understand the artistic and socio-political change that the experiments of the avant-garde triggered in the 20th century.” Dreams are always avant-garde because they are not subject to rules and logic. Similar to the avant-gardes themselves, they disappeared as quickly as they appeared, but always left traces behind. It is not for nothing that the Surrealists were heavily influenced by Freud’s writings. Dalí himself even developed a real obsession with Freud from the 1920s onwards. Its leading figures, such as Breton, combined this psychoanalytic component with elements of Marxism, which led them to the assumption that dreams contained not only an individual, but also a collective and socio-political dimension.

However, the surrealist exhibits on display are not strictly demarcated from works of other related art movements; on the contrary: at the beginning of the exhibition there are works by Dadaist artists that were of central importance for the development of surrealism. Experimental short films by Andy Warhol, for example, will also be shown – including one in which he films his sleeping lover for several minutes. There are also excerpts from literary works by representatives of the US Beat movement such as Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Borroughs – which is obvious, as their works were also permeated by the belief in the transgressive power of dreams and accordingly strongly influenced by the radical approaches of their surrealist role models.

Another centerpiece of the exhibition are photographs by the American photographer and journalist Lee Miller. She was immersed in the surrealist scene in Paris in the 1920s and worked as a war photographer for the US military from 1944 onwards. The exhibition mainly shows pictures from the last days of the war. Among them is the iconographic photo in which she sits in Hitler’s bathtub and absentmindedly scrubs her back.

The exhibition objects are framed by a modern and simple interior that breaks with the baroque surroundings of the log house and offers the avant-garde exhibits appropriate space. In a sense, the archive within the city is as alien as dreams within the unimaginative reality.

“Archive of Dreams”, until September 1st, Archive of the Avant-Gardes – Egidio Marzona (ADA), Dresden