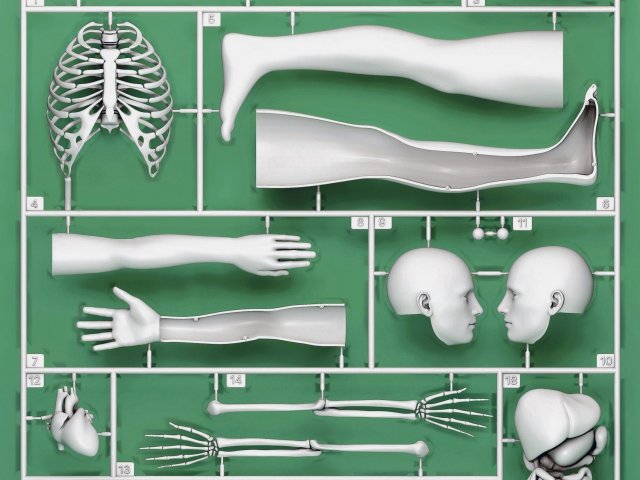

Foto: akg/Ikon Images/Magictorch

Gali Jaffe, what do you say about people complaining that gender issues are now supposedly politicizing a field like archeology?

Jaffe: It depends on how you look at it. As a trans person, your very existence is a political statement in some parts of the world. But let’s take a step back: archeology is a science of facts. It’s not about politics, because the findings and therefore the facts are there. The only question is whether they want to see them or not.

But it’s also about how you deal with finds, right?

Yes. Much of the way we have looked at gender in archeology, and to some extent still do, dates back to the 19th century. If a grave was found with a sword, it was automatically assumed to have belonged to a man. Of course, there weren’t the resources to do DNA testing or anything like that back then. But no other option was simply considered. The problem is often the approach of those who research the finds, because they don’t give other interpretations a chance.

Interview

Private

Gali Jaffe is an archaeologist with a master’s degree from Tel Aviv University. She worked at various excavations, the Israel Antiquities Authority and in adult education. In 2021 she moved to Berlin, where she works as a city and museum guide and gives lectures on gender and archeology. She is currently working on publishing a book about archaeological findings regarding trans people.

How far back in history can we go and find concepts of gender that are non-binary and fixed?

The thing about archeology is that the further back you go, the harder it is to establish certain facts. Because if you go back, say, 2500 years, you’ll usually find some form of written record. But further into the past you reach a point where you no longer have any documents. How far can we imagine ourselves into the minds of people 10,000 or 20,000 years ago if we don’t even have any documentation? This is difficult.

Is there a specific point in history when you can say with some certainty that non-binary or transgender people existed?

In the book I want to publish on the subject, I start around 3000 BC. So that was about five thousand years ago. We have evidence of the gala from this time. These were Sumerian priests, and they may have been what we would today call transgender. But as I said, you have to be very careful in archaeology. I don’t want to commit if I don’t have crucial information in front of me. That’s why I like to leave question marks.

Can you explain in more detail what the Gala is all about?

The Gala were a sect of priests who, as far as we know, were associated with the goddess Ishtar. In principle, Ishtar could also be described as transgender. We have poems about Ishtar and the goddess Inanna, respectively, an earlier incarnation: both of them could change their gender and also change the gender of people. But we assume that according to mythology they did this more to annoy people. There were probably different priestly sects, one for the male side and one for the female side. But the Gala had very feminine make-up, wore feminine jewelry and dresses, and, as far as we can tell, they had high-pitched voices. This could perhaps be due to castration. We have figures of them, we have cuneiform writings about the gala. They really existed. The only question is how to interpret this information and artifacts.

And what is your interpretation?

We are probably dealing with men who dressed like women, performed feminine rituals and worshiped a trans goddess. But does that mean that they were transgender, like I am transgender, which means to me that there are aspects of me that make me dysphoric, that I’m uncomfortable with? I don’t know it. Did the Gala behave this way because they were forced to do so, perhaps as part of a religious ceremony? That is possible. In any case, we cannot say with certainty that these people were transgender. But we can certainly say that the society in which they lived was open to the idea that gender can change.

Do you have any other examples?

Yes, of course. In the minds of the ancient Egyptians, women had to change gender in order to reach the afterlife. That’s exciting, isn’t it? The most famous example is, of course, Elagabalus, who was the emperor of Rome in the second century. Or perhaps I should say Empress of Rome? We know that Elagabalus actually stood outside taverns at night to seduce men! And she asked to be called a lady and not a man. We also find information regarding the idea of gender change among the Vikings. For example, there are gravestones that say that anyone who tampers with the grave will become a woman. So in this context, changing gender identity is a negative thing, a punishment. But at least the Vikings believed that it was possible to change gender. In the 14th century – but this is more history than archeology – a Jewish scholar named ben Kalonymus wrote a long poem lamenting that God made him a man rather than a woman.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DailyWords look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Can we compare understandings of gender from history with our concepts today?

We should not try to impose our understanding of gender on ancient cultures. That doesn’t work. In the past, people never experienced the things that modern medicine makes possible. For example, I take hormones myself. As a result, I became a completely different person, everything about me changed. We cannot claim that people once thought the way we do if they simply did not have the same conditions.

Since we find other concepts of gender in the past, the following question arises: Where is it that, until recently, at least in Europe, we viewed gender as binary and fixed?

Christianity. The religion. I admit: For me, religion is a system to control people. An example of this is the idea that you must have a wife and children to go to heaven. I have nothing against starting a family; I have a partner with whom I had four children – before my transition. We’re still together. But there were and are also other lifestyles that should also be accepted.

You came out as a trans woman in 2021. Does your own story have anything to do with your interest in this topic in the field of archaeology?

When you come out as trans, you are suddenly confronted with a variety of new concepts. I didn’t understand some of it, and if I don’t understand something, I read about it. I also believe that everything has an archeology – ask me a question and I’ll find an archaeological reference! In this respect, I was sure that there was also an archeology of Gender gives. And in fact, the more I researched, the more material I found on this topic.

Since when has the topic of gender been studied in archaeology?

Gender is a fairly new topic in archaeology; it has only been researched for around 20 years. But today there is more and more work being done on this, which can be seen, for example, in the fact that there are more and more talks on gender issues at the meeting of the European Association of Archeologists.

Sometimes transphobic people write on social networks: No matter what someone identifies as now, when people dig up their skeleton in 1000 years, they will know what the person’s “true gender” is. What is your response to such statements?

I’m an archaeologist, so believe me, I’ve heard this kind of thing before. My answer: Let’s assume that I myself were mummified and my tissue was preserved. Then at some point you would find a body with a female breast and a male sexual organ. And now? The skeleton simply says nothing about a person’s gender. It never did. In addition, the archaeologists of the future would probably not only find my skeleton anyway, but my entire grave, including a tombstone and perhaps a few personal things that would really say something about my gender.