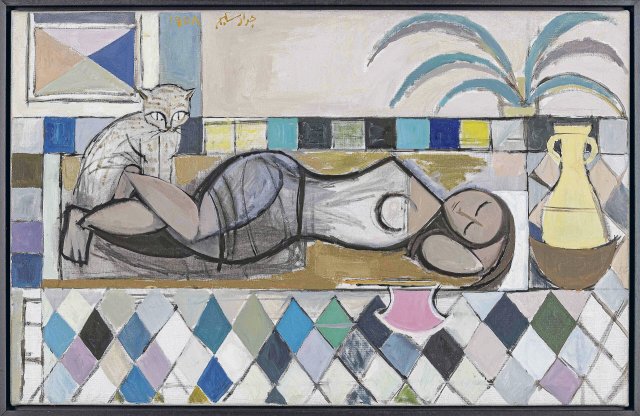

Jewad Selim, Alqailoula, oil on canvas, 1958

Photo: © Estate Jewab Selim

Everyone has certainly heard of heroes of modern art such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse or Fernand Léger. However, artists such as Abdallah Benanteur, Inji Efflatoun or Huguette Caland will be much less familiar to most people. With the extensive show “Présences Arabes” (Arabic Presences), the Paris Musée d’Art Moderne (MAM) has now taken on the task of making the contribution of more than 130 artists from North Africa and West Asia to the development of modernism visible close.

As Morad Montazami, one of the three curators, explains in an interview with »nd«, it has long been his dream to bring modernism from the Arab world to the Paris museums. The cosmopolitan generation from which he comes is now very visible in contemporary art – there is currently a very remarkable exhibition by the Franco-Algerian artist Mohamed Bourouissa in the Palais de Tokyo next door – but when it comes to 20th century art, they dominate white artists still dominate the exhibition events.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The exhibition at MAM, based on extensive research, follows classic museographic conventions when presenting the works. Accordingly, the curators divide their revision of the modern canon into four chronologically ordered chapters. It becomes clear how unavoidable it was for Arab artists at the beginning of the 20th century to engage with Orientalism, as the Arab world in European painting mostly only served as an exotic background backdrop seemingly frozen in time, made up of palm trees and camels and kasbahs. This choice of motif can still be heard in the painting “Fez” (before 1921) by the Algerian Azouaou Mammeri. His image of the Medina of Fez is divided by a city wall. To the right, in front of the city gates, a traditionally dressed man has sat down with his two dromedaries. It is a classic orientalist choice of motif, but this is an indigenous orientalism that represents a first step towards appropriating one’s own image.

This appropriation accelerates in the works of the second section of the exhibition, which is dedicated to the period of independence of the first Arab countries, such as Lebanon in 1943 or Iraq in 1958. This era also saw the first avant-garde departures, such as those of the Egyptian surrealists around the group “Art et liberté” (Art and Freedom). The painting “Lunchtime” (1956) by the Egyptian Fatima Arargi, which shows a group of workers having lunch, comes from a different tradition. Although Arargi used clothing to identify her workers as part of the same social group, she also endowed them with individual characteristics such as different head shapes, hairstyles and beards. Unlike socialist realism, it does not show a heroically steeled proletariat building the country; instead, the workers take a break with her.

The curators also examine the exhibition history of Arab artists in Paris. Works from important gallery exhibitions are shown in color-contrasting sections. Reference is made, for example, to the show by the Algerian artist Baya, who was only 16 years old at the time, in the Maeght Gallery in 1947. The participation of Arab artists in major exhibitions is also being discussed. While countries such as Tunisia with Safia Ferhat and Lebanon with Shafic Abboud took part in the 1959 Paris Biennale, there was no contribution from Algeria, which would only become independent from France in 1962 and had been at war with the colonial power since 1954. Algerian artists, however, are well represented in the third part of the exhibition, which is dedicated to decolonization. One focus is on the AOUCHEM (tattoo) group: the artists involved, such as Choukri Mesli and Denis Martinez, set out to find an original Algerian contribution to abstract art after independence. In their works, they were inspired by the country’s rich visual resources, such as the prehistoric cave paintings in Tassili or the patterns in the tattoos of the indigenous Amazigh population.

The final fourth part takes us back to the 1970s and 1980s. The art of this era is also often determined by political themes, such as the racism of French society or the Palestinian liberation movement, which entered into the choice of motifs of many Arab artists from 1967 at the latest. The collages of the anarchist magazine “Le Désir Libertaire” about the exiled Iraqi Abdul Kader El Janabi, which are based on the historical avant-garde, are captivating with a tongue-in-cheek lightness. For example, the magazine captioned a picture of Karl Marx with his daughter Jenny, who is wearing a necklace with a cross around her neck: “Religion is the opium of the family.”

»Présence Arabes« offers the opportunity to discover remarkable artistic works and practices and in the process does a bit of justice to several generations of previously little-noticed artists. Because the exhibition highlights the connection between the artists on display and the city of Paris, for example through exile, participation in exhibitions or visits to art schools, the city on the Seine also becomes visible as a capital of a transnational interweaving of artistic modernity.

»Arab presences. Modern Art and decolonizationuntil August 25th, Musée d’Art Moderne, Paris, and »Mohamed Bourouissa: Signal«bis zum 30. Juni, Palais de Tokyo, Paris

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

sbobetsbobet88judi bola judi bola akun demo slot link sbobet