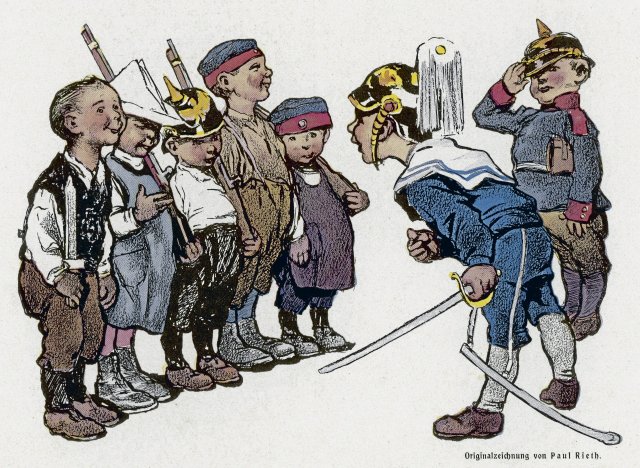

Caricature by Paul Rieth (1871–1925) on the military training of young people in Germany

Photo: IMAGO/Gemini Collection

I’m wearing a dress. I’m standing at a cart in the yard of our house. He is big, bigger than Marie, as big as a house. Marie is the nanny, she wears red coral around her neck, round red coral. Now Marie is sitting on the drawbar and rocking. Ilse comes through the farm gate with her nanny. Ilse runs up to me and offers me her hand. We stand like that for a while and look at each other curiously. The strange nanny is talking to Marie. Now she calls Ilse: ‘Don’t stand there, that’s a Jew.'” An episode from a German childhood around 1900. It is written in a book by Ernst Toller that was published almost a hundred years ago.

Such books are gathering dust, says the market, which has reduced literature to a quickly consumed disposable product. But the sentence “Don’t stop there, that’s a Jew,” which could also be thought and pronounced in today’s Germany, shows that old books are not old at all and dead authors are our contemporaries.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

Who was Ernst Toller? Born in 1893 in Samotschin, on the extreme eastern edge of the German Empire. A playwright whose plays found a huge international audience in the 1920s. When Toller was not yet forty, he wrote his autobiography, “A Youth in Germany.” The man had truly experienced incredible things and plenty of them. Toller’s readers learn that a young German who was regularly insulted and insulted as a Jew could still feel patriotic. When the German Empire went to war against the hated Western democracies in 1914, the student volunteered to serve at the front. And gets to know the consequences of the steel storms: “One night we hear screams, as if a person is suffering terrible pain, then everything is quiet. “Someone will be killed,” we think. After an hour the screams come back. Now it won’t stop. Not this night. Not the next night. Naked and wordless, the scream whimpers, we don’t know whether it comes from the throat of a German or a Frenchman. The cry lives for itself, it accuses the earth and the sky. We press our fists against our ears so as not to hear the whining, it doesn’t help, the scream spins like a top in our heads, it stretches the minutes into hours, the hours into years. We dry up and grow old between clay and clay.”

“A Youth in Germany” is not a chronological description; it consists of an infinite number of short episodes. A montage of splinters, impressions, pointed experiences, associations. Ernst Piper, editor of the new edition, has enriched the book with a detailed explanation of the actual passage of time, which helps to classify Toller’s highlights historically. In the middle of the war, the author realizes that those who are being massacred in their thousands are not French, English or German, but human beings. His patriotism turns into suffering for Germany, whose elite willingly sacrifices its youth.

The young Toller sets out to find a spiritual way out of the “terrible turmoil of the times”. At a meeting of high-ranking intellectuals, sociologist Max Weber demands that the population finally be involved in political decisions. But most others seek salvation in religion, in esotericism. In a letter to the editor, an anonymous mother wishes that Toller, who has now become known as an author and dissident, be tied to a shell crater and torn apart by English bullets. A sensible Germany is not in sight.

In 1918 the situation was hopeless, more and more Germans were starving, and many workers and sailors refused to serve. The war is lost, the Kaiser abdicates, Germany becomes a democracy. In November 1918, socialists attempted a Soviet-style revolution. The company fails, but hope arises in Munich, of all places, where Toller lives. A Soviet republic is proclaimed there. When they came into military distress shortly afterwards, the declared pacifist Toller was made military commander. A few times his people were able to repulse the reactionary troops, but after four weeks the Soviet Republic was defeated.

Why this? Toller sees the way the various left-wing groups treat each other as a crucial reason for this. There are the representatives of the SPD, which governs from Berlin; the representatives of the USPD, which split off from the SPD because it was entangled with the forces of old Germany and capitalism; the representatives of the Moscow-oriented communists. After the murder of Kurt Eisner by a ethnic anti-Semite, Toller becomes chairman of the Bavarian USPD. On the left there are constant, tangible arguments with and against each other. Even when the opponents of the Soviet Republic stand at the gates of Munich and their downfall threatens, the Left cannot agree on anything.

But according to Toller, the mentality of most workers is also a problem. They are too used to blind obedience, they consider the exclusion of their own responsibility as discipline and brutal gestures as strength; They are not ready enough for democracy. The defeat of the Munich Soviet Republic is devastating, the revenge of the victors is terrible. Leaders and supporters of the republic are immediately shot – or after appropriate judgments by a thoroughly corrupt judiciary. Toller manages to hide, but is discovered. Because celebrities like Max Weber campaigned for him, he only had to serve a prison sentence. Toller made a career from prison. His plays were performed all over Europe and when he was released he was a celebrated literary star.

In 1933, after the Nazis took power, Toller published a second edition of his autobiography with an exiled publisher. The added afterword states that one cannot understand the events of 1933 without knowledge of what happened in Germany in 1918/19. Above all, what was meant was the hopeless disunity of the left, which robbed it of its political strength at crucial moments. But Toller also blamed a certain human trait for the success of her opponents, such as the extreme right: “the indolence of the heart,” which leads people to allow what they don’t want. “A Youth in Germany” – a fantastic book, from yesterday for today.

Ernst Toller: A youth in Germany. Edited by Ernst Piper. The Other Library, 346 pages, hardcover, €48.

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

judi bola judi bola online pragmatic play