Was there something? This fountain in Heilbronn is called the “Comedian’s Fountain.”

Photo: imago/Schöning

Here, in Germany, the beautiful word “coming to terms with the past” was invented to describe the rapid relegation of crimes committed during the Nazi era into the memory hole. The technique that is meant by this is not entirely uncomplicated: not wanting to remember and at the same time having to officially remind people of the duty to remember, wanting to erase the memory and at the same time officially organizing commemorative rituals that have frozen for so long with the same empty commemorative phrases, until the last one Those who actually want to remember give in and, as in “Asterix and the Arvernian Shield”, exclaim: “There is no Aleschia! We don’t wipe where this Aleschia lies.”

People in this country have always been in a hurry to give things and events a new name if they have proven to be somehow disadvantageous or had a bad reputation in the past. That’s why the era of National Socialism is now called either “the dark chapter”, “the difficult years” or “the age of totalitarianism” (which also has the advantage that the GDR, co-founded by surviving victims of German fascism, is equated with German fascism can be).

This is still a proven practice today: garbage is now called “recyclable material,” the German police chief is referred to as “home minister,” and capitalism has been renamed “free market.” If barbarism has already proven to be unpleasant for many, at least its name should have a friendly ring to it. It’s “the sound that touches”, as the well-known piano manufacturer Bösendorfer already knew (company’s advertising slogan, 2009).

In the past, when it was the Holocaust that had a bad reputation from one day to the next, or that had the impression that it had somehow turned out to be disadvantageous, which some Germans noticed as early as May 1945, it was the streets , which were given a new name. Now, “after the war” (as the first years after liberation from fascism were called), some people suddenly, for some inexplicable reason, no longer wanted an “Adolf Hitler Square” in their community, especially not in the center, where the old oak, the village restaurant and the picturesque little church have their original location. In May 1945, even the local council’s once most zealous supporters of the demand that the old village square be dedicated to the popular and dashing National Socialist Chancellor surprisingly spoke out in favor of an immediate renaming. Which could have been due to the fact that the esteemed leader had briefly lost his reputation “after the war” – that is, when the Germans felt like victims (which they have been happy to do ever since) -.

In my birthplace, the sleepy Baden-Württemberg town of Heilbronn am Neckar, known for its vineyards, its pretty town hall with the astronomical clock and its extremely reactionary population, there is a tendency to get rid of everything that could be reminiscent of the “Hitler era” as quickly and without a trace as possible , was reflected in a very special way in the renaming of streets: that suddenly people no longer wanted the largest and most representative street, the “Adolf-Hitler-Allee”, which runs through the middle of the city center, to have the name of, let’s say , controversial politician carries, seems understandable. They made do by simply leaving out the name, which was laden with all sorts of bad things (about which they didn’t want to know anything more): “Allee”. Wasn’t it easier to remember now than the complicated name from before? Simply “avenue”. Wasn’t that simpler, more concise, more minimalist? Also, hmm, more modern, contemporary, so to speak, more future-proof by completely omitting a name?

After all, there was the same need for a name change in almost all German cities at that time: the man, this Hitler, had finally promised victory against the Americans and Russians, world domination by Germany and the extermination of the Jews and, to the great disappointment of the majority of the population, on None of these promises can be kept in the end. Now they wanted to get back at the cheeky rascal, who was suddenly no longer the beloved leader, but just the worthless “Austrian private,” by quickly erasing not only his name, but also those of his helpers and accomplices everywhere.

In Heilbronn, the lively renaming activity that began in May 1945 produced a few strange results: it was decided that “Hegelstrasse” would henceforth be called “Schlegelstrasse”; probably because in their overzealousness one philosopher was apparently considered a crypto- or pre-Nazi, while the name of a romantic, Catholic enthusiast and fighter for the emancipation of women and Jews was considered appropriate. (And you only had to add three letters to the street sign.) But the ingratiation with the hated Allies was by no means over: “Hermann-Göring-Straße” and “Horst-Wessel-Straße” became over Night – Abracadabra, simsalabim! – the “Marxstrasse” and the “Heinrich-Heine-Strasse”. What is significant here is that they apparently followed a rather bold pattern (“Look at the list of burnt poets. Or a communist. We need two names”): they wanted to rush their own goodness or prepotent desire to make amends to the new rulers through a pushy approach demonstrate proactive obedience. You were innocent, you weren’t a Nazi, you never had anything against Jews, communists, mockers, satirists, curmudgeons or clever people, that is. Faster than anyone could say “Holocaust,” you were purified, or you didn’t have a guilty conscience at all. In any case, an effort was made to stop automatically standing at attention and clicking one’s heels, as the servile employee Schlemmer, a caricature of the German Nazi and authoritarian character, did in Billy Wilder’s film comedy “One, Two, Three.”

Ironically, two of the most hated radical left German intellectuals under the Führer, both from Jewish families, were now to become the new namesakes for the two Heilbronn streets that had previously been used to honor high-ranking Nazis. Apparently the hope was that such an obscene self-cleaning attempt, carried out in retrospect, would make the crimes in which one was involved forgotten at rocket speed, so to speak. Both streets are still called that today. The “Allee” also bravely continues to bear its non-binding name, which can be added to at any time if necessary. But today, hardly anyone passing by in Heilbronn’s pedestrian zone will be able to give you any reasonable information about who Heinrich Heine was.

By the way: In the Wikipedia entry on the Bösendorfer piano manufacturer (Vienna) mentioned above, it is noticeable that there is a gap in the chapter on the company’s history, which surprisingly covers the years between 1932 (“the sons joined the company”) and 1944 (“bomb attack”) ). But that’s only on the sidelines. Wink, wink.

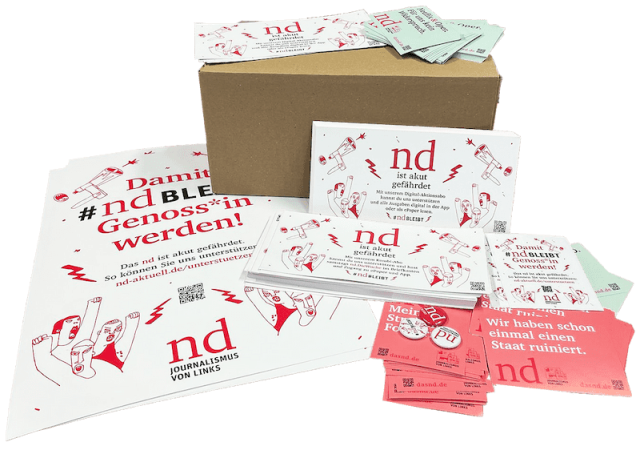

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

judi bola online judi bola online judi bola judi bola