This pub went under with its landlord.

Photo: Kai Ehlers

This story of the “death of a harbor pub” is told from the end – in the unusual form of a photo novel. Claus-Otto Menden inherited the management of a traditional harbor pub in Wyk on the North Sea island of Föhr that has existed for five generations. One Christmas Eve the pub remains locked and the landlord cannot be found. The sniffer dogs track him down to the jetty. He “went into the water” and drowned himself in the ice-cold North Sea. This is followed by 13 chapters with titles such as “At Aunt Herta’s,” “Work Ambition Alcohol America,” and “Dog Life,” with over 200 illustrations. The text consists largely of anonymized conversations that the author Kai Ehlers had with over 40 people over ten years.

What happened? The camera’s gaze searches for clues, voyeuristically penetrating the dead man’s apartment, which has long since been emptied. Then the camera finds it – in the adjacent bar. Flensburg Pilsener is no longer served here, but the interior is still there, souvenirs from five generations of seafarers. The pub is called “Faith, Love, Hope,” but everyone calls it “At Aunt Herta.” The former guests talk about what it was like back then, while the camera captures the curiosities and the rooms are filled to the ceiling.

Officially it was called “Faith, Love, Hope,” but everyone called it “At Aunt Herta’s.”

Photo: Kai Ehlers

It’s as if the author had opened the bar again for one last shift and listened to the regulars at the bar in the cigarette smoke during a long night with countless “Köm”, the popular aquavit. Fragmented and never linear, the anonymized voices tell the story of this strange place that perished with its host.

We learn all sorts of things about the heyday of the seafaring pub, which dates back to around the 1960s, which was also the economic peak of merchant shipping and local fishing. During this time, “At Aunt Herta’s” established her reputation. The anecdotes about the single mother Herta Menden (her husband left her for the mainland with a younger woman), who runs the shop with her sister, create a picture of a female bar regime that successfully ran the harbor pub for decades before she left Takeover by son Claus-Otto is coming to an end.

The bar crowd consisted of locals as well as strangers and tourists, and ordinary sailors who were neither. In addition to the obligatory sailor romance, there is also the romanticization of the great social equalizer, the pub, in which proletarians in dungarees and bank managers in ties share the counter. The two sisters are portrayed as strict and hardened as well as sensitive and caring.

Aunt Herta in particular is transfigured in the memories as a mother: “She could listen and give advice here and there, comfort a little, and then you could at least get your worries off your chest (…) Sometimes she even got you into your head Arm taken.” Aunt Herta was an authority figure and could do something different if necessary. When some guests come up with a drinking game in which the dice decide when you have to pee and when you can go pee, one of the other players stands up in violation of the rules. “Then Aunt Herta came, the wet Feudel in her hand, slapped the tall blonde twice in the face, left, slap, right, slap, with the Feud and ordered: ‘Sit down!’ That’s how Aunt Herta had her shop under control.” Her through decades The status she earned by working night shifts at the bar made it possible for her to be honored with a burial at sea after her death, which was “actually only allowed for sailors and captains.”

“The often admired maritime decoration was put together over decades by local sailors,” is how the pub once advertised it. However, the illustrations of the objects in the book soon make it clear that these are not simply seafarers’ souvenirs, as things like these appear next to sailor’s hats and ship’s bells an artistically decorated walrus tusk from the 19th century, a stuffed crocodile, a dagger with a swastika, a shrunken head and others that do not fit the term “decoration”. There are objects whose historical context is German colonialism and National Socialism. At one point in the book they are appropriately referred to as “mute witnesses.” What would they talk about if they could talk?

As befits a photo novel, there are text boxes around the illustrations, filled with the voices of the bar patrons and occasional observations from the narrator. Do the texts comment on the images or do the images comment on the text? The book asks this question using the rather unpopular form of the photo novel and deliberately leaves it unanswered.

The documentary-artistic narrative style, which author and director Kai Ehlers has already used impressively in his films, is particularly suitable for this. In “Free State Center” (2019) he tells the real story of the Nazi eugenics victim Ernst Otto Karl Grassmé, who was interned and forcibly sterilized by the National Socialists and denied compensation after 1945. The film interweaves the sound of Grassmé’s read letters to Federal Republic authorities with film footage from the moorland to which he retreated in the post-war period. In the film as in the book, the author’s attitude is not imposed in the narrator’s commentary; it can be seen in the composition of documentary images and the voices of contemporary witnesses. However, the historical and political situatedness of the images and texts remains.

The strange objects on the walls of the pub are individually brought in front of the camera and photographed. However, they are not completely revealed to the reading public: the colors of the photographs – in constantly changing formats and scales – are reversed, we only see the negatives of the images. The camera view is no longer voyeuristic here; it seems to want to protect the objects from exotic looks. Provenance, the question of origin and ownership history, played no role in the pub: “Nobody knows where the things come from anymore. We didn’t want to know anything about it.” It cannot be verified if someone says about an Asian-looking wooden mask: “I bought that at a market. In Jakarta, Indonesia.”

What is impressive is how Ehlers manages to ask questions about the ethics of exhibiting artifacts of, for example, colonial historical origins without moralizingly overwriting the anecdotes of his interlocutors. His approach does not level out the different positions, voices and time levels. He transcribes the interviews authentically in the North German dialect.

But he also speaks out in carefully chosen places so that we are not misled about his authorship. To give an example: At one point the narrator’s commentary goes into more detail about the biography of the Wyk honorary citizen and Wehrmacht commander in the Netherlands, Friedrich Christiansen. We learn about Christiansen’s responsibility for the deportation of Dutch partisans and Jews, as well as his overzealous rehabilitation by the Wyk city council after the war. Allegedly because of his “love and attachment to his homeland” and “his positive human traits,” Friedrich-Christiansen-Strasse was dedicated to him again in 1951. The biographical digression follows an anecdote in which Christiansen was also remembered as a family friend and a benevolent perpetrator. It is an indication that the stories of contemporary witnesses cannot always be trusted – even where the narrator does not provide a historical fact check.

Instead of giving us another North German regional crime thriller, “Death of a Harbor Bar” tells about more than the sudden death of an innkeeper. When reading it you often have to think of W. G. Sebald and his idea of a “natural history of destruction”. Our gaze is drawn to the forgotten legacies of a destructive history that goes beyond the tragic individual fate. It’s good that the author photographed the collection again and asked his contemporaries about it – before everything was cleared out, disposed of and forgotten, as if it were just furniture from a dead person’s apartment.

Kai Ehlers: A song about life. Death of a harbor bar. With photographs by Kai Ehlers and Grischa Schmitz. Textem-Verlag, 300 pages, br., €16.90.

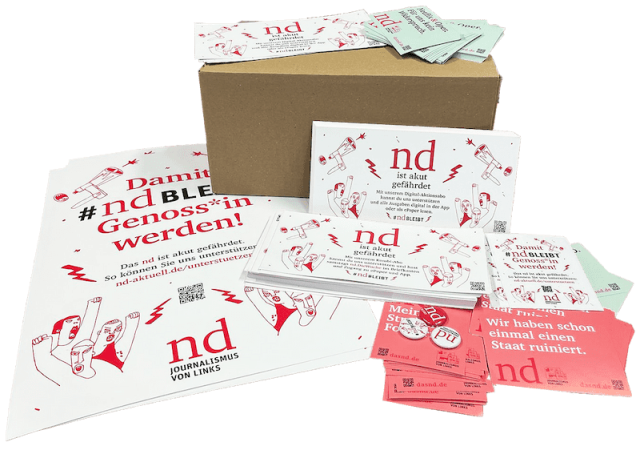

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

judi bola sbobet link sbobet judi bola online