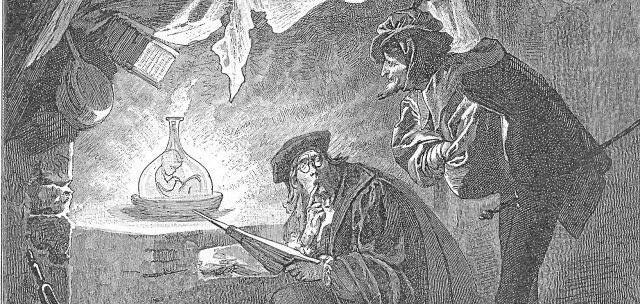

Already in Goethe’s “Faust II” the artificially created intelligence appears in the form of the homunculus, the little human in the glass.

Photo: wikimedia.org

In a simulation, scientists recently observed how so-called language models (programs that work similarly to ChatGPT) make military and diplomatic decisions. These escalated surprisingly quickly and did not shy away from the use of nuclear weapons.

There is no question: the use of AI in a military context is dangerous and AI knows neither human compassion nor morality. As long as the AI cannot fire weapons automatically, it is still people who decide about life and death. Nevertheless, in view of such devastating areas of application, we must be concerned with the question of how intelligent machines can be, what autonomy such intelligence can achieve and whether they could ultimately turn against humanity itself.

However, the writer Michael Wildenhain does not deal with specific areas of application of AI in his recently published first non-fiction book “A Short History of Artificial Intelligence”. “The focus is on the question of the extent to which AI systems, measured against the general human scale, can be viewed as intelligent and whether speaking of the consciousness of a machine makes sense – or not,” is how the author himself formulates the aim of his book. Wildenhain, known as a novelist, draws on the resources of his time studying computer science and philosophy, but allows the literary elements to flow into the form and content. The short volume is structured as a kind of theater piece in three acts.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

In the first act he begins with intelligent but non-human creatures in literary history, or rather: with the fear of such creatures. The disembodied homunculus from Goethe’s “Faust II” and Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” are mentioned here. However, both fictional characters are missing something that is later discussed as essential for human intelligence and consciousness. Goethe’s homunculus, as a spirit in a vial, lacks a body with which he could interact with things in the world. In the course of the brief overview of the history of AI, we get to know some theorists according to whom human intelligence can only be conceived with a “body-in-the-world”.

Shelley’s literary monster, on the other hand, has a body but remains excluded from human community. In terms of the history of technology, this is perhaps analogous to the robot, which has a body but acts without understanding the context of a situation.

But is “artificial intelligence” actually an intelligence? The computer scientist John McCarthy was the first to coin the term “artificial intelligence” in 1955, still in the early stages of computer development. In the second act it becomes both mathematical-technical and philosophical. Among other things, cognitivism is presented, which equates the human brain with a digital computer, as well as the opposing position of the philosopher John Searle that information processing in the brain and computer is structurally different. Connectionism, in turn, believes that it can technically recreate the human brain in the form of neural networks. The artificial neurons fire depending on whether they receive the input signal 0 or 1. However, it has not yet been possible to build a digital twin of a human brain in this way. In any case, the “Human Brain Project”, which ended in 2023, was unable to achieve this goal.

The success story of AI in recent years has been in the area of large language models, which became known primarily with the ChatGPT program. This tool is able to process a very large amount of language, but beyond that it is a bit like the homunculus: it does not live in the world, that is, it has no factual knowledge whatsoever and is not placed in any context. Such a language model can perhaps discuss war and peace, what an atomic bomb is and the suffering it causes, but it understands nothing about it. »Developing an intention on their own, for example to take over the world, is beyond the reach of the chatbot or the AI system. It ‘knows’ nothing about world domination, it ‘knows’ 0 and 1 and their many combinations,” writes Wildenhain.

Skeptical minds may object: Not yet. Emergence enters the stage in the third act. Those who believe in emergence assume that by increasing the complexity of a system, something new can emerge that is greater than the sum of its parts. The author argues, however, that on the one hand this would be a “blatant violation of the causal closure of the physical world” and, on the other hand, that a consciousness would somehow have to arise that is not identical to that of the programmer.

And ultimately, according to Wildenhain, with the emergence problem you end up with the body-soul dualism of Western philosophy or a religious theme. If we ask ourselves whether the machine can develop consciousness, then we first have to know what consciousness actually is. And where the concept of intelligence was already unclear, that of consciousness is even more so. But if consciousness is to be thought of materialistically, that is, not outside of a body – and therefore religiously – then human consciousness can only be an “autosuggestion” that the human brain constantly generates. The machine, on the other hand, even if it were to learn to reproduce and program itself, would always have to be initiated by humans.

However, if we believe in spiritual entities that exist beyond the physical world, then machines can also be intelligent and have consciousness, says Wildenhain, thus relegating the discussion to the sphere of theology.

Michael Wildenhain: A short history of artificial intelligence. Klett-Cotta 2024, 120 pages, €16.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet sbobet88 sbobet pragmatic play