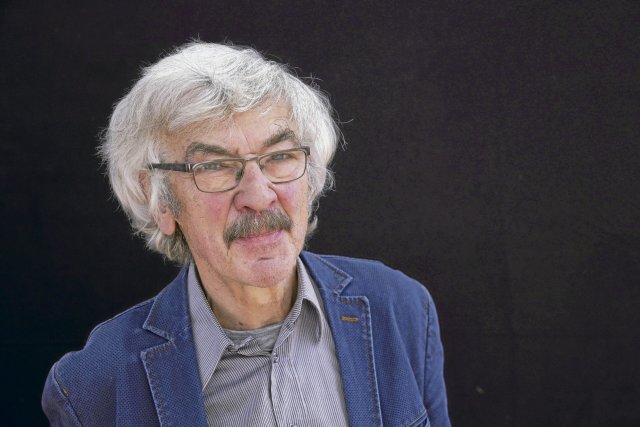

The writer Christoph Hein is demanding not only in his literature, but also in public speaking.

Photo: imago/Gerhard Leber

Yes or no – a basic genetic question: Will you primarily be an agreeer in life, or will distance become your very own format? Christoph Hein: “Even before I was in a position to seriously ask myself whether and how I should get involved in society, the state told me that it did not value my participation.” A pastor’s son in the GDR: no chance of graduating from high school. Living in the East, he went to school in West Berlin and would soon flee for good.

The construction of the wall, however, sealed the forced stay in the unloved, presumptuous “dwarf state”. This is how a soul trained itself in good time – into that said distance. The “only possible” basic attitude for an intellectual. And its ethical responsibility? “He must report what he learned. He has to report ruthlessly, that’s actually all.” This is how Hein became a prominent German writer.

In his books he describes people in crumbling shelters. The demanding adventure is placed between the individual and the oppressive society: suffering to recognize the true situation – but still loving, remaining in search of light. In the story “The Foreign Friend,” for example, there is the doctor Claudia who only reads the private classified ads in the boring GDR newspapers – a departure from the prevailing big lie, a journey inwards. What you do can be a great force, but what you decidedly no longer do can be a greater force.

nd.Kompakt – our daily newsletter

Our daily newsletter nd.Compact brings order to the news madness. Every day you will receive an overview of the most exciting stories from the world editorial staff. Get your free subscription here.

Fellow writer Ingo Schulze recalls the time of East Germany’s awakening when Gorbachev, the great hero of the retreat, stirred hearts, and Schulze calls Hein’s novel “Horn’s End” from 1985: “Literature that gave us space to breathe, to speak. Steps from which there was no going back.« The novel’s hero, Horn, perishes because of the SED’s cold-heartedness – as if the obligation to be absurdly Kafkaesque was part of the party program. The fate of the book: two years of struggle against censorship. Then Elmar Faber, head of Aufbau-Verlag, simply had it printed. Without permission. A one-time process. The authorities then demanded a “solution to the Hein case”, i.e.: get rid of the damage, preferably across the border! Classically cynical. Just domination. Hein stayed.

Born in Heinzendorf, Silesia in 1944, shyness was always like a very durable steel cable. He is a brittle Protestant who walks into each group and speaks with prudence – which is not the opposite of decisiveness. Yes, also speaks. The writer is demanding not only in his literature (“The Tango Player,” “Willenbrock,” “Conquisition of Land,” “Mrs. Paula Trousseau,” “Weiskern’s Estate”) but also in public speaking. Trained in the only valid place of teaching and learning – the school of self-experimentation.

At the Xth Writers’ Congress of the GDR in 1987, Hein boldly said: “Censorship is illegal because it is unconstitutional.” He proclaimed Leipzig, the city where he studied, as a hero city in November 1989 at the historic rally on Berlin’s Alexanderplatz; His play “The Knights of the Round Table” had previously become a rage-inflaming parable of the SED agony in Dresden. Even in modern German times, the writer’s anger did not leave him. He was the first president of the reunited PEN club. His commitment represented a vain hope: with the end of the GDR there could be a time of mutual enlightenment and complementarity. Nothing there.

There is a measuredness in his work that is extremely violent; There is a perceptual precision whose even pulse tells of a tremor. Stubborn reason rejects obsequious faith in prevailing rules of behavior. In the novel “A Garden in His Early Childhood,” it is the former high school principal Richard Zurek who is rejected. His son, who had been part of the anti-state underground in the Federal Republic for years, had died. Shot? Suicide? In his search for this son, whom he lost long before his death, the old West German Zurek will also lose faith in the order that he had loyally served.

This novel is perhaps Hein’s most rebellious book. Zurek must realize that errors of loyalty are the worst. This fright eats into the banality of everyday processes and wears us down. In the end, Zurek revokes his official oath in front of students at his former high school: “I swore to conscientiously uphold the Basic Law and all laws of the country. But since the state does not uphold its own laws, I am released from my oath of office.”

When we talk about the novelist Hein, we also have to talk about the playwright. The book with the collected pieces has 726 pages. It combines 16 plays. So the author comes from the theater – the paradox, of course, is that at some point the dramaturgy no longer took over his plays, but primarily his novels.

The play “Cromwell” (1980) describes the path of an idealist to dictator. Members of the “Southern Border Command” are sitting in the GDR premiere in Eisenach (specifically away from Berlin). In uniform. Hein is startled. In a conversation after the performance: You stare at the author without saying a word. Increased pulse. The highest-ranking officer: He was stunned by what Hein had written. Silence in the hall. Destruction? But then the commander’s postscript: He felt exactly “what I had put into words” (Hein), border protection was pointless “since there was nothing left to defend.”

The most loyal as the most desperate – the GDR’s conceptual drama as a tragedy, broken out in loyal hearts that even a uniform no longer protected from surrender. Surrender to the bitter truth. Hein’s theater is not shimmering shimmer, but rather flaming shiller. And Schiller is: sensuality of the argument. Against forgetting. And this forgetting begins with questionable historical memory – which is fatally good because it glosses things over. For proof, read the memoirs of those who were once powerful (including the GDR): they often lack character in order to look into the ashes of their own years.

I’m thinking of Hein’s novel “Trutz.” The 20th century in two intersecting family stories. The Great Terror in the Soviet Union. A narrative along a cold, bullet-riddled wall: Stalinism. This forced enthusiasm of a cadre party that trained millions to tolerate and cut them off from sources of self-respect. This spying on one’s own followers. This evil tendency to give short shrift. The truth: silenced. But a single sound cannot be erased; it is the powerful silence of the victims. This sound travels through the book as a continuous sound. And through the times. Also through our present.

Hein’s narrative work offers probing stories about a top priority of the bourgeois that is worth preserving: retaining a sense of the status of the individual. The hardest thing is the most cultural thing: those who don’t defend themselves against the world don’t feel it. This is literature against those whose consciousness is stuck with a vignette: a permanent position on the politically right side. German history? The only thing that matters is the quarry bill; Only the Shards Court makes valid judgments.

Hein also writes poems. Hans-Eckardt Wenzel set some of them to music and sang them; the CD is called “Masks”. In one of these melancholic verses: the writer’s self-ironic information about what he has understood about the world over the course of his life – “only a little and everything too late”. Today Christoph Hein turns 80 years old.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership application now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

judi bola online sbobet sbobet88 sbobet88