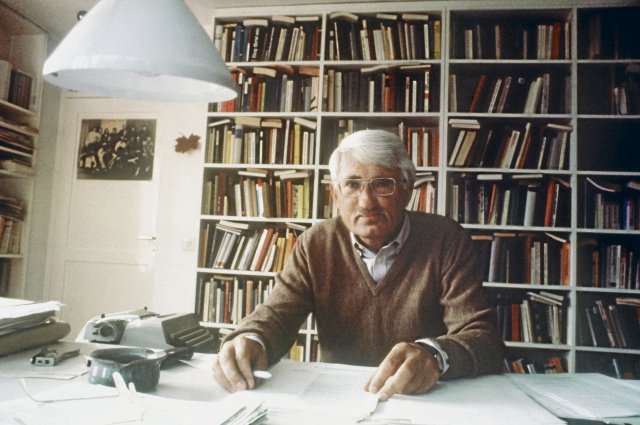

Jürgen Habermas, social philosopher and sociologist of the “Frankfurt School,” in August 1981 in his home in Starnberg

Photo: dpa/Roland Witschel

Theory means “making the intellectual silhouette of your own generation stand out more clearly,” writes Philipp Felsch. One can expect nothing less from the cultural historian, who has almost created his own genre with his outstanding portraits of German-language philosophy. The focus is always not on individual people, but on landscapes of thought in their entirety. This also applies to his new book about Jürgen Habermas. Behind the almost maudlin cover image of the philosopher looking out the living room window is not a home story or a conciliatory retrospective, but rather a conflict-laden intellectual post-war history of Germany.

Habermas is still the most important intellectual in the Federal Republic. He holds a position for which there is no successor in sight. On the one hand, this has a lot to do with the fact that the overall demand for the polymath type is falling. Today, specialists are more in demand. Their expertise is often so fragmented that it is difficult to translate it back into a perspective on society as a whole – be it only at the national level, not to mention the global level, which is more than ever opposed to becoming uniform to bring the term. On the other hand, newspapers, book publishers and television companies are hardly interested in reproducing the format of the great philosopher due to their digitally changed way of working. If one does not want to romanticize this change, then it is important to soberly assess the relationship between academic philosophy and its media and political effectiveness. No one could do this more clearly and precisely than Habermas himself.

Serious idealism

Habermas once called the “farewell to profundity,” as Felsch quotes it, precisely this requirement to take philosophy and social criticism out of the realm of speculation and bring them into the light of the transparent and interpersonally communicable arguments of science. No longer depth, higher insights or the authority of philosophical professionals, but the rational argument that can be understood step by step should prevail. Only in discourse, in talking seriously to one another, does “truth” change from an institutional imposition to a positive lived experience. As Habermas himself said: “Whenever we mean what we say, we claim that what is said is true or correct or truthful; This brings a piece of ideality into our everyday lives.”

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

How important such a core of serious idealism is for a successful social life can only be assessed in retrospect, from its end, when it disappears from everyday political life and transforms itself back into a cynical consciousness. But to this day the discussion also revolves around whether this delicate operation of implanting an idealistic rationality into everyday life was even possible or desirable.

Because the objections to such a project were and are countless: Isn’t politics always about power relationships that cannot be resolved sensibly as a matter of principle? Isn’t rational politics a contradiction in terms? Isn’t combative, political action dependent on a surplus of creative energy that arises precisely in the murky waters of irrational depth? The informal coercion of the better argument, on the other hand, remains strangely toothless and will most likely end up being ground beyond recognition by the mills of the institutions. The often “counterfactual assumption,” as Habermas calls it, that my counterpart could be just as serious as me is then assumed to be bourgeois self-deception. Can we really cut out everything metaphorical and hyperbolic from the language of politics, so that in the end decisions are made “only “straightly”, i.e. with a straightforward, transparent rationality? And would that be a world we would even want to live in?

Without tricks and false bottoms

Yes, says Habermas – and in this sense he always defended a very classic program of “mass enlightenment”. And not only against the re-emerging national myths of the new right, but also against left-wing theories that resisted a rational formulation of their content. Wasn’t there such depth in the older critical theory of the Frankfurt School, which Habermas wanted to thoroughly work on over the course of his life and put on a transparent basis, when it warned in the name of dialectics of the danger of identifying thinking? Thinking without tricks and false ground – and above all: without hiding gaps and abysses in the argument when they arise – remains a constant feature of his work. As Axel Honneth once put it: “The formal structure of Habermas’ theory is oriented towards intersubjective understanding, not towards stylistic resistance to purposive rationality.” Even today, this cannot be assumed unquestioningly for all theories.

But self-understanding about the state of philosophy also means that this rational thinking was often wrong in terms of content. Felsch gives some examples. Habermas’ assessment of the civil rights movement in the USA already gives one pause if the philosopher did not want to recognize any particular revolutionary potential in the movement. His famous overreaction at the “University and Democracy” congress, when the misplaced keyword “left-wing fascism” was suddenly mentioned in a discussion about militant forms of action, should not be missing from this list. From today’s perspective, the assessment of the new French philosophy of structuralism as “young conservatives” was just as wrong. This doesn’t seem very consistent, not least given his own early program of thinking “with Heidegger against Heidegger” – a formulation that must seem almost perplexing in today’s changed scientific landscape.

Most recently, Habermas’ plea for a negotiated solution to the Ukraine war was widely criticized from both sides of the spectrum: some accused him of not recognizing the similarities with the wars surrounding the breakup of Yugoslavia, which would justify Western intervention then as now. The criticism from the other side was that the implementation of an international legal order by a supposedly neutral world police, which was already envisaged at the time, had long since lost all credibility and only amounted to the primacy of Western capital interests. The hope for the USA as a new, progressive power, which Habermas probably held for a long time, has been dashed even more fundamentally in the last 20 years.

Democratic way of thinking

Habermas is perhaps relevant today not so much because of his concrete interventions, but because of the democratic form of his thinking. This does not mean anything radical or grassroots democratic, where quality and quantity merge, but rather the opposite: institutional knowledge, checked by several mutually controlling layers, which is not based on final determinations, but is always at the level of the state of the art type of philosophy must justify. The recently deceased Oskar Negt already reported on the “tremendous amount of effort in justification” that Habermas must have demanded of himself and his students in the seminar.

What remains is a mixed outcome. Because not only foreign policy and the relationship to French theory fell victim to this claim to complete justification, but also the legacy of Marxism. His “Reconstruction of Historical Materialism” was conceptually so strict and thorough that little that was recognizable remained of what was reconstructed in this way. In many respects, Marx’s crisis theory also no longer experienced the exposure of its rational core by Habermas in his work on late capitalism. Many radical leftists – “radicalized by Adorno’s theory and disappointed by Adorno’s practice,” as Felsch writes – have not forgiven him for this. Nevertheless, you can no longer go back on these interventions – you can’t leave philosophy at will if you no longer like the result. But that seems to be exactly Habermas’s lesson: Anyone who doesn’t want to pursue politics and science in a populist manner must stick to the right argument in good times as well as in bad times, regardless of whether it comes in handy at the time. Ultimately, it is this position that makes Habermas’ relevance today.

Philipp Felsch: The philosopher. Habermas and us. Propylaea, 256 p., hardcover, €24.

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

judi bola link sbobet judi bola judi bola online