Hacks knew it and Goethe already suspected it: Bonaparte was our comrade.

Photo: Collection IM/KHARBINE-TAPABOR

How did the anthology “The Defense of Goethe” come about?

Of all the books on Goethe on the market, I was missing one by Peter Hacks. The Weimar museum shops are incomplete without him.

In fact, there are countless Goethe biographies and text collections from Hermann Hesse to Sigrid Damm to Thomas Mann, but so far none of Hacks.

He wrote so much, and above all: so well, about Goethe. The public hardly knows anything about it apart from the monodrama “A Conversation in the Stein House…”. In order to change that and because he once called his essayistic work a single “defense of Goethe,” I suggested this reading edition to the publisher. So the title was set. As bonus material there are two reviews by Goethe himself and an essay by me on the question of why today’s art funding prevents art.

Interview

Marlon Grohn, born in 1984, studied German and sociology and is a journalist. He published the books “Communism for Adults” (2019), “Hate from Above, Hate from Below. Class Struggle on the Internet” (2021) and, together with Dietmar Dath, the collection “Hegel to go. Sensible Quotes« (2020). The brochure “Hegel’s “Beautiful Soul” and its relationship to evil” was recently published. He lives in Cologne.

What makes Hacks’ writings about Goethe so interesting?

What’s special about him is that he’s very philologically precise where necessary, but always keeps the bigger picture in mind. And in contrast to literary critics and German scholars, Hacks speaks the German language. His Goethe essays are also a sociology of German conditions around 1800. These in turn are always an opportunity for Hacks to engage with his present. He is just as far removed from the dullness and dullness of today’s language as he is from the expectability and barrenness of today’s judgments. Hacks shares insights, but with a linguistic and conceptual artistry rarely encountered.

Why did Hacks, as a communist, refer so vehemently to Goethe?

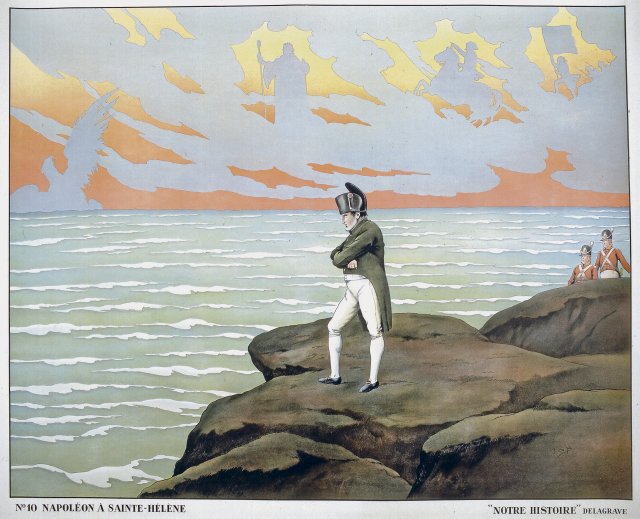

For him, the debate with Goethe is a political issue. He admires Goethe not only because of his poetic skills, but also because of his political stance. Goethe did not pay much attention to the political judgments of his time and sided with Napoleonic progress, which was very unpopular with the great majority of Germans. Hacks also saw Bonapartism as progress and suggests that a left that does not do the same will be incapable of socialism.

Do you think that this collection of essays will change something and that Hacks will be rediscovered as an important interpreter of Goethe?

I hope so. What I’m actually concerned with is a matter of the future: Hacks was shaped by the GDR and his work was only fully possible and understandable under socialism. But for now we are still living under capitalism and I would like to see people actually learn from all the “left-wing stupidities” (Lenin) and not repeat them next time. I think hacks are extremely important for this.

But it’s pretty unlikely that there will be a hacks movement left, right?

The “Defense of Goethe” is hopefully just a beginning. Hacks is intended to become more exoteric: his work offers points of reference for readers of classical music on the one hand, and for leftists on the other, who otherwise tend to adhere to “critical criticism”, i.e. Pohrt, Adorno and so on. If in the future it were possible to read not only “Das Kapital”, “Dialectics of Enlightenment”, “Objectpoint” and “The Society of the Spectacle”, but also hacks, that would be considerable progress.

To what extent does Goethe play a role here?

The connecting point of the above is Hegel. And with it Goethe too. A lot could be learned today just from his attitude and his way of making art. Of course, a simple “Back to Goethe” is not enough. You don’t have to throw away what you have already recognized and appreciated. It is about a practice like theory that has gone through modernity, dialectical materialism, critical theory, and also through their errors, but has absorbed and enriched what is correct. You can’t just shake off such traditions, you can only process them. Such processing can take place through art, philosophy and politics.

What does that mean specifically?

There is a difference whether one looks at Marx from the perspective of Goethe and Hegel or from the theories of the “New Left”. Hacks stood not only on the shoulders of Goethe, but also on those of Lukács and Brecht, who in turn stood on those of Hegel and Marx. In the future there should be a left that has already learned to stand on the shoulders of hacks.

Do you have great hope for that?

As a Goethe and Hacks defender you are an optimist and say: What is necessary will happen. Socialism is a must, so you will have to read hacks. Lukács went to the party, Hacks to the GDR, Goethe to Italy. You should also take these steps as messages to today: If you put all three together, you’re pretty close to the right thing.

Hacks really struggled with the romantics. As for Goethe, they were not just a nuisance for him, but also an opportunity to wage journalistic feuds.

Hacks calls Goethe’s texts about Romanticism “counter-Romantic battle writings.” This is what many of Hacks’ essays are about. You only fully understand this when you see it as part of a fight against romanticism and the evil it caused – in politics as well as art.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

In your afterword you write that classical music has no interest in criticism. What does hacks have against criticism?

It is enough for him to praise Goethe. Criticism of the current situation is already included in this defense of the classical. But Hacks goes beyond criticism. Anyone who defends classical music already knows that society is poorly equipped and does not limit themselves to just pointing out its mistakes. Contrary to the critics, the classics have left behind well-crafted works and realistic concepts capable of changing the world.

But didn’t Hacks take a very critical look at the Romantics?

He considers the Romantics to be completely overrated and also to be incompetents – but he does not consider them worthy of criticism. He simply describes them. He not only sets his sights on the literary era of Romanticism, but also the present. His defense of Goethe also means a fight against neo-romantics like Heiner Müller. Not that he doesn’t also reject their political positions. But he is concerned with their inability to complete the work, their subjectivism. That miller, for example, saw the progress of art in the destruction of classical works, the destruction of genres. The bomber squadron as an aesthetic program – that seemed a bit poor to Hacks.

Back to the “movement” again: Hacks sees classical music as one »Political party«. So does this lead to the motto “Classics of all countries, unite”?

Don’t worry, the classics from all countries have long been united. Compared to the other proletarians, they have it quite easy: they are a very small number. Anyone who still has a clear idea anywhere in the world today and knows how to convey it honestly is automatically part of the Classical International, KI.

Peter Hacks: The Defense of Goethe. Essays on Classics, ed. and with a postscript by Marlon Grohn. Eulenspiegel-Verlag, 272 pages, br., 20 €.

judi bola link sbobet sbobet88 judi bola