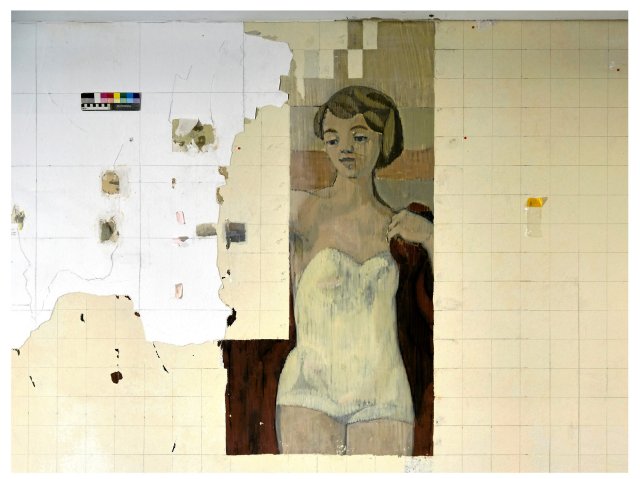

A real backbreaking job, but one that is worth it: centimeter by centimeter, an early work by Richter, “Joie de vivre,” is being recreated.

Photo: Andreas Rost

Regaining lost joy in life can be an arduous task. In the German Hygiene Museum Dresden (DHMD), protective masks are even necessary for this, as is precision archaeological work with a scalpel and soft brush. It is a process that involves the stench of chemicals and is quite tiring on the eyes. It also requires a lot of time and a steady hand. Albrecht Körber and his colleague Susann Förster only manage to increase the “joy of life” by 1000 square centimeters each day.

Körber and Förster are restorers and are currently uncovering a mural that bears this very title. It shows people in the countryside: at a picnic, on the beach, dancing. It was painted by Gerhard Richter, now one of the most important visual artists in the world, and a student at the University of Fine Arts (HfBK) in Dresden at the time of its creation, three quarters of a century ago. The mural in a stairwell of the Hygiene Museum, painted in 1956, was his diploma thesis. It earned him some recognition: a grade of “very good,” an aspirant position, and an Adiparter. “Not everyone managed to do that,” says Ivo Mohrmann, who is currently a professor at the HfBK and heads the course in which restorers are also trained.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DieWoche look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The fact that two of them currently have to deal with Richter’s picture is because it was painted over in 1979. At that time, the former Dresden graduate had already been a professor at the art academy in Düsseldorf for several years. He left the GDR immediately after the wall was built. After his “joie de vivre” had been whitewashed, the wall was finally used for texts that gave visitors introductory explanations about the changing special exhibitions. Because it was designed in matching colors, eleven layers of color were added to the diploma painting over the years. Most recently, says restorer Körber, “they were painted yellow.”

The first ideas for uncovering the picture again existed as early as 1994. At that time, however, Richter rejected it. A year earlier, a large retrospective of his pictures had been shown in Bonn. The celebrated artist may have feared that the youth work from the socialist era could “seem disturbing in retrospect,” says Dietmar Elger, head of the Gerhard Richter Archive at the Dresden State Art Collections. Given the bitter debates about art from the GDR, this would be understandable. The picture has never been forgotten, emphasizes Elger. It was frequently reproduced and was considered a “central work of Richter’s Dresden period.” The great media interest in the current exposure gives an idea of the commotion such an action would have caused a few years after the political upheaval. Three decades have now passed. The view of the art created in the GDR is more differentiated. It is widely accepted as “part of the cultural heritage,” says Philip Kurz from the Wüstenrot Foundation, with whose support a number of large murals from the GDR era have already been restored, such as the mosaic “Unity of the Working Class and the Founding of the GDR” by Josep Renau at a prefabricated building in Halle-Neustadt. The foundation also contributes part of the 220,000 euros for the restoration of Richter’s mural. Dietmar Elger notes that he will be 92 years old this Friday: “At that age you see many things differently and more calmly.”

For the Dresden Hygiene Museum, Richter’s approval of the exposition of the “joie de vivre” is a fortunate circumstance. The house, whose origins go back to an international hygiene exhibition led by the mouthwash manufacturer Karl August Lingner in 1911, has repeatedly dealt with its eventful history, such as its involvement in the spread of racial ideology in the Nazi state. A special exhibition that opens on March 8th and is entitled “VEB Museum” will focus on the role of the house in the GDR. The fact that Richter’s mural is now being partially made visible again is certainly symbolic, says DHMD director Iris Edenheiser: It represents “one of the central historical layers” in the museum’s past. The fact that it is only partially restored is also well thought out and is intended to illustrate that history has moved beyond the time it was created. “You should continue to see that in the picture in the future,” says Edenheiser. In the best case, around a third of the 62 square meter image will be uncovered again. A prerequisite is that the specially developed restorative technology proves itself.

Albrecht Köster is confident in this regard. He and his colleague tried various things to remove the eleven layers of paint over the “joie de vivre”. Because one of them is a wax paint that acts like a separating layer, the top layer can be carefully removed. The restorers worked on the remaining five layers with scalpels or tried to remove them with heat; both without success. This was finally achieved by a mixture of different solvents. They soften the alkyd resin primer that was placed over the painting, but not the casein paints from which Richter created it. The chemical mixture is applied to ten by ten centimeter pieces of fleece and pressed against the wall. Then “we set the alarm for 25 to 30 minutes,” says Körber. The top layers then bubble and can be removed with great care. The actual picture, says the restorer, “is not damaged in any way.”

What emerges square by square amazes even connoisseurs. All previous reproductions were in black and white, says Elger. “We had no idea at all about the color.” Now it becomes clear that Richter worked with pastel, reserved colors – and in a remarkable technique that until now had only been guessed at. He placed one vertical brush stroke next to the other on the 15 meter wide wall. The technique, known as “carpet painting,” which has been used since the mid-19th century, was brought back from exile in France by Richter’s Dresden teacher Heinz Lohmar, a communist persecuted by the Nazis. As a teacher at the Dresden University, which was founded in 1951, Lohmar enabled his students to “stand out from shallow propaganda,” says HfBK Professor Mohrmann, using such painting styles, among other things. There are no figures of workers and farmers or scenes of socialist construction in Richter’s mural. Museum director Edenheiser tends to draw comparisons to paintings such as “Breakfast in the Green,” which Edouard Manet painted in 1863.

Visitors to the Dresden Museum can already make their own comparisons. Albrecht Körber and Susann Förster, who are working in a partially glazed cube under the guests’ eyes, have uncovered the first sections of the painting: here a face, there two feet – details of a bathing scene with a nude on the back and colorful towels. The “joie de vivre” will return to the Dresden Museum piece by piece by October.

Become a member of the nd.Genossenschaft!

Since January 1, 2022, the »nd« will be published as an independent left-wing newspaper owned by the staff and readers. Be there and support media diversity and visible left-wing positions as a cooperative member. Fill out the membership form now.

More information on www.dasnd.de/genossenschaft

sbobet slot demo demo slot x500 pragmatic play