Enjoy the cooperation. What is more important for us humans?

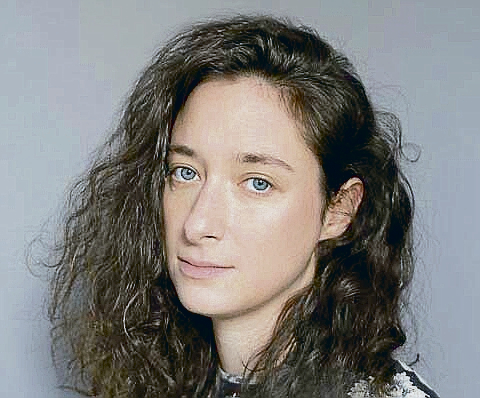

Photo: Wfilm

»Love Annelie « – With these words, the letters that the protagonists of their new film write to them and which they read in the film begin. How did you get the idea of using this form instead of the usual interviews or free statements in front of the camera?

I am a fan of giving protagonists a lot of freedom of design and giving them the chance to use films for themselves, for what they want to tell. The form of writing gives more time to find an answer. You have the chance to think about how you want to tell your story and present in front of the camera without being delivered without surprising questions. It is also a bit more poetic than just talking down. I prefer that very much, especially with the stories in off.

You only hear a question in the film that you ask the protagonist: “What is care for you?” Have you asked further questions as the basis for the letters?

Yes, the letters were created for weeks and months. I actually sent very specific questions to all protagonists and gave them the opportunity to tell other things, so they were completely free.

Interview

private

Annelie Boroş (Born 1991) studied documentary and television journalism at the University of Television and Film Munich. Already their first works such as “Mars Closer”, “F32.2” and “Fuck White Tears” were shown at international festivals and received several awards. Your new documentary “The Tender Revolution” is dedicated to the topic of care.

Does the personal salutation of the letters also indicate that you want to be neutral observers not only like other documentary films, but are personally involved?

I didn’t make it so consciously, but I wouldn’t have done it if I hadn’t added a personal level to the film anyway. I have also decided to tell that my very good friend and roommate Kathrin committed suicide during the research for the film. When it happened, I paused and took care of myself and this whole situation. But the idea quickly arose: what is crashed into my life is exactly the topic that I deal with in the film project. That’s why I ask a very personal question to the beginning of the film: in which world would Kathrin have lived in? Or is there a world in which suicide would not have been your only way out? From this, an even more personal and emotional bond for the stories of the protagonists has been created, and the form of the letter reinforces.

In the end they address Kathrin themselves. A message to her late girlfriend?

I started working on the film before the suicide. He is included for everyone who has the feeling and suffer from the fact that we don’t worry well enough in this society. He is aimed at everyone who sees a deficiency and should be a little declaration of love for them. Even on Kathrin, because I very much hope that it would have been in your sense to make this film like this. I had exchanged a lot about the project with her. It is a nice idea that it is a gift for you.

How did you find your protagonists, all of whom are conspicuously eloquent?

I found it in very different ways and over a very long period of time. Arnold, who cares for his severely disabled son, I have via Gabriele Winkler’s book “Care Revolution” discovered. The social scientist wonders what can be done against the fact that care is so far behind in our society. Your idea is to combine different battles, and committed caregivers like Arnold play an important role.

The Polish 24-hour nurse Bożena was also in public with her history. She complained against her agency and won the process. Since then, she has organized herself unionized to support other nurses. It was very important to me to find a person who can also speak critically about their situation – which is risky because they run the risk of no longer finding a job.

The disabled activist Samuel is a friend of a friend who told me during my research. We also became friends immediately. Through him I wanted to focus on the question: How is it actually for people who rely more on help than others? At the same time, Samuel is a caring that is currently building an inclusive house project in which everyone takes care of each other.

The doctor and indigenous climate activist from Peru, Amanda, I met through a friend. She has put care for nature at the center of her work.

How did the decision come to include a climate activist who actually falls out of the topic in the film?

It was totally important to me to address that it is not just about care for people, but about care for everything that lives. We are all dependent on our environment and our environment, and we are only doing well when the systems around us are healthy. You always think: some people need care; I needed her as a child and maybe I need her again in old age. But we need them all the time. The food intake is already part of Care. We need a healthy planet so that we have food and are not delivered disasters. Amanda, for example, travels to the Ahr Valley and meets people who are affected by the flood.

To what extent does your own Romanian family background play a role for the film?

24-hour nursing staff from Romania provided my Romanian and German grandma in Germany. As a child, I had a close relationship with my grandma’s supervisor, and she had to leave her own familiar life behind to make money. This Care Drain is abstruse: nurses come to Western Europe from their Eastern European countries, but their own parents and children have no one who cares about them. Bożena came to Germany as a seasonal worker and, like many Romanians, picked cucumbers. Producing food so that people are cared for can also be seen as very relevant care work.

How did it come to draw boundaries with intimate scenes, for example? Have you coordinated with the protagonists what the camera can show?

We discussed beforehand what we wanted to do. In a film about care, care should be clearly visible – with everything that goes with it. I have already set this off when choosing the protagonists. Samuel has expressed his wish to contribute to reducing fear of contact. He suggested a lot of what he wanted to show, for example how he wakes up, does noise exercises with his assistant and how he goes into the sauna with his friends, carrying him into it naked. I gave the participating time and offered to look at scenes afterwards and, if necessary, to take veto. This door was always open.

The protagonists also had very clear limits: Arnold’s son, for example, is not naked in the bathtub. And the old lady, who is looked after by Bożena, said: “We can go to the cemetery together and cook and eat together, but I don’t want to be filmed how I will be washed.”

So you have found a caring handling of the protagonists. This is not a matter of course in the documentary. I have already heard the statement from director: Then you can no longer make films if you have to clarify everything with the participants.

Some filmmakers tend to emphasize this gradient: I am the filmmaker, you are in front of the camera, and only I know how this film should be. I defend myself against this approach. I am happy to tie the protagonists, ask them: What do you need this film for? What is your interest in participating? Especially with such an intimate topic, it would be incredibly uncomfortable to put me and say: Look at what I made for a great film. It is very important to me that the protagonists can use the film for themselves. There is also something caring in it.

“The tender revolution”, Germany 2025. Director: Annelie Boroş. 93 min. Heavy of the theatrical release: August 14th.

judi bola link sbobet sbobet sbobet88