Trapped in the waiting room: In “Twin Peaks,” the man from another location (Michael J. Andersen) meets investigator Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan).

Foto: Imago/Everett Collection

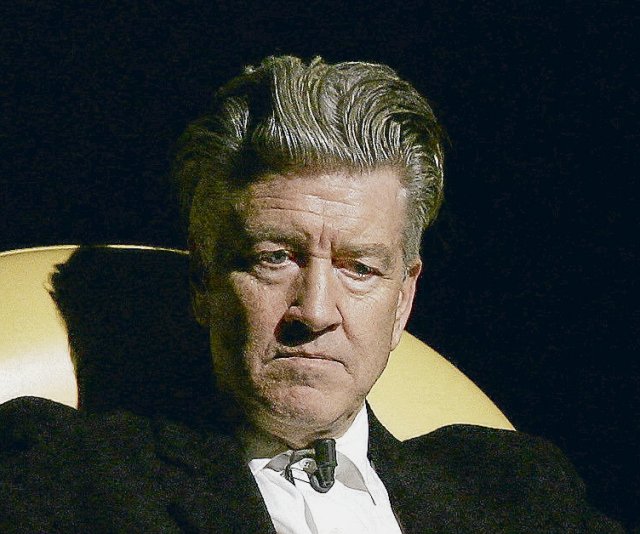

No, it is of course no coincidence that the vocabulary we encounter in the countless reviews of his films, also in the disparaging comments about his works and in the praises of the cinema creator David Lynch himself, seems as if it came from a textbook for Psychoanalysis. The uncanny and the unconscious, dreams and nightmares, the gaze of others, the dissolution of the self in a surreal world and the dissolution of one’s own perception – these are the motifs that we encounter in David Lynch’s world of images and ideas.

The adherence to these motifs – from which a separate cosmos emerged, which the journalist Georg Seeßlen once dubbed “Lynchville” -, the courage to be mysterious and the artistic consistency are what Lynch has, contrary to the rules of probabilities that almost always exist in Hollywood are in force, making him one of the most influential and important directors of the second half of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. This filmmaker, whose origins in the field of fine art are evident and which he could never completely abandon, was responsible for only two handful of feature films for the cinema as a director (mostly also as a screenwriter, occasionally as a supporting actor), which were made between 1977 and came to the screen in 2006.

Photo: afp

“Eraserhead” was the name of Lynch’s debut feature-length film, which was sometimes denounced as a horror film, but like all of his works, it confidently evades genre boundaries and style attributions. Jack Nance, known for his continuous collaboration with Lynch, played the main character Henry Spencer, who is forced to take care of his deformed child. The nightmarish reality only gives way to the protagonist’s nightmarish fantasies: deformed bodies appear, excessive violence breaks out, a head rolls – literally.

This was followed by “The Elephant Man” with Anthony Hopkins, the literary adaptation “Dune – The Desert Planet” and “Blue Velvet” full of violent sexuality, then – touchingly beautiful – “Wild at Heart”, the kaleidoscopic “Lost Highway”, “A True Story” full of unexpected abysses and the melancholic, dark dream journey “Mulholland Drive”. “Inland Empire” – between the experience of violence and the compulsion to repeat – was Lynch’s last film almost twenty years ago. Each of them enjoys cult status today.

And the tenth of his films? “Twins Peaks – Fire Walk with Me” from 1992 is the prequel and actually just the cinematographic accessory to the series of the same name, which, without exaggeration, has the status of a work of the century. With this work, Lynch has achieved what many series productions claim but cannot achieve: he has translated the complexity of the plot, the inventiveness and the pleasure in experimenting with form from sophisticated novels into a format suitable for television. David Lynch is the epic poet of television.

nd.DieWoche – our weekly newsletter

With our weekly newsletter nd.DailyWords look at the most important topics of the week and read them Highlights our Saturday edition on Friday. Get your free subscription here.

The pilot episode first appeared on US television in 1990. What unfolded over the next two years and two seasons was the panorama of a traumatized small town. A murder had happened – and now, riddled with all sorts of bizarre and mystical elements, cracks appeared in a glossy surface. Twenty-five years later, Lynch picked up where he left off and produced a third season of his series that exposes the uncanny in a homey community. “The owls are not what they seem,” it says at one point. No, there is almost nothing here as it seems. The boundaries of the fantastic have been far exceeded. But in everyday life, in society, in ourselves, little is as it seems. Hardly anyone knew how to capture this in moving images like David Lynch.

It was not uncommon for the accusation to be leveled against psychoanalysis that it was merely bourgeois self-reflection and ultimately a completely apolitical institution. David Lynch also made it easy for his critics. Isn’t his work evidence of uninhibited aestheticism? Isn’t his obsessive interest in people’s inner lives, in the abysses within people, an excuse not to deal with the conditions under which they have to live in film? And behind all the astonishment that his films trigger, isn’t there the drawback that much of the Lynchian flood of images has to remain incomprehensible and therefore becomes terrible, beautiful decoration? Added to this is his peculiar commitment to the so-called transcendental meditation and the esoteric and finance-hungry sect that stands behind it.

But, to paraphrase Heiner Müller: The film is smarter than any camera and also than anyone who occupies the space behind it. Lynch’s films are the cruel, unadorned counter-images to the incessant promises of progress of a fed-up society; his nightmares are the appropriate contrast to the American dream, which is an illusion of a different kind. Contrary to the mysteriousness and isolation of Lynch’s oeuvre, his grotesque characters reveal a deeper impression of the humiliated and insulted of the present than is ever apparent in the pseudo-realism of mainstream Hollywood cinema.

After a serious illness, the artist David Lynch died on Wednesday, shortly before his 79th birthday.

link sbobet sbobet88 link sbobet judi bola