What a drug is remains a matter of definition: opium was once a drug

Photo: imago/UIG/nd

“The Great Intoxication” – the title of Helena Barop’s book is succinct and reveals little about its content. The first and second subtitles provide information: The “global history” of drugs “from the 19th century to today” is told here and the question of “why drugs are criminalized” is examined.

The book was published in 2023, before the Cannabis Act (CanG) came into force. Nevertheless, it appears at just the right time. The book dispels myths about the dangers of drugs and their users – just at the moment when the normality with which drugs are criminalized begins to crumble, as it says in the introduction.

Historical reconstruction

In the last chapter, which acts as an epilogue, Helena Barop slips out of her role as a historian and positions herself socio-politically. She asks: “Which elements of drug policy can we use? And what can go away?” In order to answer these questions, as will be shown below, a historical reconstruction is essential. Because, as Adorno emphasized in “Remarks on “The Authoritarian Personality,” resentments and prejudices are perpetuated especially when their origins are not the subject of reflection. The historian Barop is also of the opinion: “An answer to the question of what drugs are and why they were criminalized can only be found by looking at the history of drug policy and the contexts in which this policy developed.”

Muckefuck: morning, unfiltered, left

nd.Muckefuck is our newsletter for Berlin in the morning. We walk through the city awake, are there when decisions are made about city politics – but also with the people who are affected by them. Muckefuck is a coffee length from Berlin – unfiltered and left-wing. Register now and always know what needs to be argued about.

But back to the beginning: The book, which has “largely no footnotes or academic jargon,” was preceded by a doctoral thesis. Helena Barop did her doctorate on the subject of “Poppy Flower Wars. “The global drug policy of the USA 1950–1979”. In view of the “never-ending requests and inquiries”, she wrote this book based on this work, which is explicitly aimed at a non-scientific audience and aims to inform and enlighten everyone who is interested (and especially those who should be interested).

In the first nine chapters, Barop traces the development of US drug policy, taking various global entanglements into account, as the titles of the book and doctoral thesis suggest. The tenth chapter contains a much shorter – in places tending to be abbreviated – history of drug policy in Germany. However, it is clear that the German narcotics law, which has existed for around 50 years, is in many respects an import from the USA.

Barop’s reconstruction of the various stages and groundbreaking decisions on the path to today’s global drug prohibition reveals the underlying interests and political background. The book shows one thing above all: today’s drug ban is a dead end that is fed by or makes use of ideological obstinacy and racist resentment. Because drugs are powerful, not only in terms of their psychoactive effects, but rather the “fear of drugs (…) can be reliably converted into political capital”. How this works exactly will be shown below using a few examples from the book.

Political issue drug

While morphine, cocaine and heroin could still be legally consumed and purchased in pharmacies in the second half of the 19th century, the first US drug ban was on opium and primarily affected one group: Chinese immigrants. Ironically, the supposedly Chinese tradition of opium smoking – according to the cliché in so-called opium dens, a “mystical and predominantly fictitious place,” as Barop writes – finds its real origin in the strategic trade of the European powers and in particular Great Britain. In the 16th century they were able to compensate for their trade deficit by importing opium to China.

In 1912, the efforts of Bishop Charles Brent, a missionary in the Philippines, to restrict the international opium trade resulted in the first international opium agreement. This marks the birth of global drug prohibition and was also made possible by racist resentments and moral panics. Then in the 1950s and 60s there was a moral panic about organized crime. Parliamentary hearings in this regard were broadcast on US television at the time and led to “the mafia being invented in front of the cameras”. The question can be asked whether such a thing as organized crime would even exist without prior bans.

Of course, Richard Nixon should not go unmentioned at this point. In 1971, the former US President declared drugs to be public enemy No. 1 and launched a “War on Drugs” with a global dimension. However, the real “enemy” was never the drugs, but rather the people who consumed them: Nixon’s drug policy became “a sharp weapon in the struggle for social control of unloved minorities.”

Many years later, former Nixon advisor John Ehrlichmann bluntly defined these groups in an interview as “the left-wing opponents of the war and the blacks.” He continued: “We knew we couldn’t ban being anti-war or being black, but by getting the public to associate hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then by criminalizing both , we were able to put pressure on these communities.”

What is clear here is that drugs were not and are not criminalized primarily because they are dangerous. The criminalization of certain substances – while others, such as alcohol and tobacco, are still legal today – always serves to control the “others”. According to Barop, drug prohibition was and is “not pharmacologically motivated, but politically”.

The eleventh chapter ties in with the history of drug criminalization and points to its current harmful consequences. The development of a racist incarceration and oppression system in the USA, which began in the mid-1970s and continues to this day, means that blacks and people of color in the USA are in prison significantly more often than their white compatriots. The reason for imprisonment is often drug use or trafficking.

But in Germany too, criminalization prevents comprehensive and honest information about responsible drug consumption. This makes it difficult for those who suffer from their own consumer behavior to get help because they fear stigmatization. A lack of substance controls and contamination, in addition to unsafe (because secret) consumption practices and stigmatization, still lead to physical deterioration and suffering for some users today. Barop states: “There is much to suggest that most drug deaths did not die and die from drugs, but from the way our society deals with drugs.”

Clearing up myths

Helena Barop wanted to write an easy-to-read and easy-to-understand book about the history of drug prohibition. She absolutely succeeded. The book impresses with the author’s extensive and detailed knowledge, which she conveys in lively language and with a good dose of irony and wit.

Barop succeeds in dispelling various prejudices and myths surrounding the topic of drugs and pointing out related problems: be it the myth of cannabis as a gateway drug; This can easily be refuted by the fact that, according to this logic, milk could also be a gateway drug because every heroin user has already been “dependent” on milk. Be it the fact that drug laws have always been an instrument of exclusion, among other things because the police check migrant people for drugs much more often than white people. Or is it the prejudice that dates back to the Nazi era that addiction is an incurable hereditary disease.

These and many other examples provide a positive answer to Barop’s final question, “Can this go away?” that she asks regarding criminalization. As experts emphasize: Drug prohibition has failed and harms individuals and society. It is high time to change that and to adopt fairer, better-functioning paths in (international) drug policy.

Helena Barop: The big rush: Why drugs are criminalized. A global history from the 19th century to today. Siedler-Verlag, 304 pages, hardcover, €26.

Basics on the topic: Michelle Alexander: The New Jim Crow. Mass Incarceration and Racism in the USA. Federal Agency for Civic Education 2017, 391 pages, €4.50.

The first US drug ban was on opium and affected one group in particular: Chinese immigrants.

–

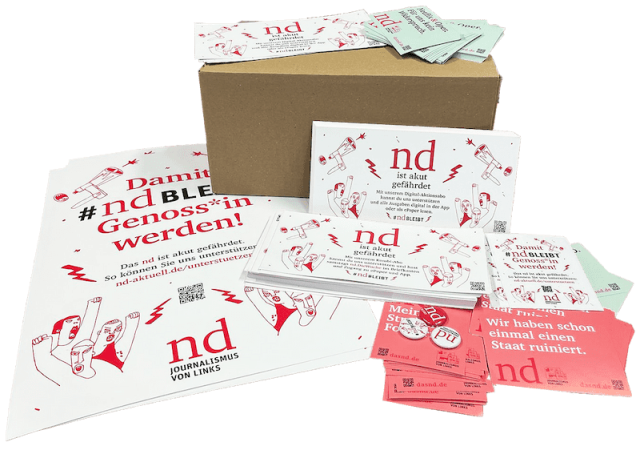

#ndstays – Get active and order a promotional package

Regardless of whether it is pubs, cafés, festivals or other meeting places – we want to become more visible and reach everyone who values independent journalism with an attitude. We have put together a campaign package with stickers, flyers, posters and buttons that you can use to get active and support your newspaper.

To the promotional package

judi bola sbobet88 judi bola online