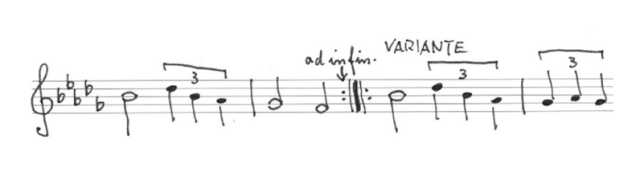

Paraphrasing Bruckner: This is how the White Stripes did it (musical notation courtesy of Jan Reichow).

Photo: Jan Reichow

Which Bruckner symphonies should you definitely hear or have heard on the composer’s 200th birthday? “All nines,” as in Beethoven or Mahler? Only if one accepts the composer’s own count, who wrote both his first symphonic attempt, the so-called Study Symphony, and the so-called »Nullte« (which was created between the first and second) has been canceled. So there are more like eleven symphonies. And then there are several different versions of some of them, with which Bruckner often responded to the assessment by other musicians, critics or the audience. Because he was a fearful and inhibited artist and suffered from feelings of inferiority throughout his life.

Today people are increasingly coming to the conclusion that the first versions, i.e. the original compositions, are to be preferred precisely because of their greater radicality, wildness or stunning immediacy, not least because Bruckner originally paid little attention to the performance conditions of his time. Especially with the Fourth, the original version of the work is essential if you want to understand the symphonic composer Bruckner and his modernity.

After his acclaimed performance as an organist in England, the second to fifth symphonies were created in a kind of creative frenzy between 1871 and 1876. Bruckner had his second and third with him when he met his hero Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, to whom he wanted to dedicate one of these two symphonies . Wagner chose that Thirdwhich Bruckner devoted to him most submissively: “Dedicated in deepest reverence to his High Honor, Mr. (sic!) Richard Wagner, the unattainable, world-famous and sublime master of poetry and music.” Phew.

The original version contains numerous references to Wagner’s works. In the finale we see how Bruckner combines a solemn chorale melody with a stylized polka. The premiere (of the middle version) at the Vienna Musikverein became the worst fiasco of Bruckner’s career. After all, Gustav Mahler attended this concert and offered to work on a piano reduction of the symphony. No coincidence, as the samples from art and folk music, such as those in the last movement of this symphony, were very close to Mahler.

Die Fourth Symphony, the “Romantic”, is probably Bruckner’s most popular work, especially because of the hunting motif in the Scherzo. However, this pleasant scherzo wasn’t even part of the work in the original version – the original scherzo was much wilder and crazier. For Wilhelm Sinkovicz, who re-examined all the symphonies for the anniversary magazine “50 Years of Brucknerhaus Linz, 200 Years of Anton Bruckner”, the final version even represents “a gross falsification of what was originally planned. The wild, unbridled gestures of the first version reveal to us the ‘modern’ composer.” Who, however, willingly sacrificed all the exuberance of his composition to suit the public taste of his time and published a well-behaved, today one would say: mainstream version of the Fourth. So: listen to the original version of the Fourth, or at least compare it to the popular final version!

The score of the Fifth was never changed by Bruckner, so there are no “versions” because it was never performed during Bruckner’s lifetime. So there was no reason to weaken or even eliminate the “future-oriented, rebellious, modern aspects” (Sinkovicz). In the finale, the combative, robust first theme and a more wistful second suddenly face four verses of a wind chorale, from which Bruckner develops a gigantic double fugue, to which he finally adds the main theme – and in the coda, Bruckner adds the main theme to this contrapuntal network first movement and ends the work with 52 bars in brutal fortissimo – that is great compositional art.

The audience will be particularly familiar with the motif from the first movement, this sequence of six notes that football fans all over the world are now singing in stadiums. Jack White from the White Stripes borrowed the motif for Bruckner’s song “Seven Nation Army”: Bruckner can confidently be called the inventor of stadium rock (or a kind of “stadium classic”); he even wrote music for tens of thousands. The radio recording of Bruckner’s Fifth from October 1942 with the Berlin Philharmonic under Wilhelm Furtwängler was broadcast on Hitler’s magnetophone as a birthday present on April 20, 1944.

Seine Seventh The symphony gave the composer the greatest audience success of his life – although not in his home town of Vienna, but in Leipzig, where the Gewandhaus Orchestra under Arthur Nikisch premiered the work in 1884. “What’s inside must come out”: Bruckner, the quip, succinctly compares his music, these “elementary musical events” (Steffen Georgi), with a volcanic eruption. An adventurous music.

One of Bruckner’s most beautiful and intense pieces is the Adagio of this symphony, entitled “very solemn and very slow.” Vladimir Jurowski needed almost 22 minutes for this magical composition, a representation of deep sadness in the face of the death of Richard Wagner: “Once I came home and was very sad, I thought to myself, the master can’t possibly live much longer, then the C sharp fell out of my head -minor theme.”

Using the solemn, somber sounding Wagner tubas that Wagner had built especially for his “Twilight of the Gods,” the Adagio culminates in a breathtaking climax. Bruckner placed it under the sign of mourning “in memory of the blessed, beloved, immortal master,” whom he had last met six months before his death: “Because Hochselber held me by the hand, I dropped to my knees, He pressed his hand to my mouth and kissed it and said: ‘O Master, I adore you!!!'” Bruckner also reports Wagner’s cool reaction: “Just calm down – Bruckner – goodnight!!!”

Die Ninth Bruckner was no longer able to complete the symphony; he was only able to complete three movements: the first movement, which strives towards a climax before collapsing uncontrollably; a ghostly scherzo and the moving Adagio revolving around the Tristan chord, which, like the first movement, moves towards an extreme climax, which erupts in a seemingly endless general pause, only to be continued in a strange E major transfiguration. In his personal copy, Gustav Mahler deleted the words “for choir, solo voices, orchestra and organ” and corrected them to “for angelic tongues, godly souls, tormented hearts and fire-purified souls.”

It cannot be emphasized enough that Bruckner’s symphonies should ideally be heard, no: experienced, live. It is precisely the excess, the gigantic, the extreme, the contradiction that creates a completely different pull in a concert than in canned music. Nevertheless, a few suggestions of recommended recordings can help build a small Bruckner audio library. First of all, the speakers: Herbert Blomstedt and the Gewandhaus Orchestra recorded all of the symphonies between 2005 and 2012 and these wonderful recordings are among my favorites. Great architecture, great intoxication; if only one complete recording, then this one.

In recent years, record companies have been working diligently towards the Bruckner anniversary and putting together older recordings into inexpensive boxes or bringing new recordings onto the market. Particularly worthy of mention are: Jakub Hrůša and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, who, in collaboration with BR Klassik, have recorded all versions and sometimes even alternative fragments of every Bruckner symphony; on the fourth CD these are the three versions and on a fourth CD even earlier versions of some passages and, particularly commendably, the so-called “Volksfest” version of the finale from 1878. There is also an excellent booklet. Markus Poschner and the Bruckner Orchestra Linz also present all of the symphonies in all versions. Christian Thielemann and the Vienna Philharmonic perform all eleven symphonies (including the “Zeroth” and the study symphony), with a rich, pleasant sound.

A reference recording is the symphonies 0–9 under Georg Tintner, an Austrian conductor of Jewish origin who emigrated to New Zealand after the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany in 1938. His recordings with orchestras from New Zealand, Scotland and Ireland are characterized by a high level of transparency and the “Viennese sound”.

If you want to hear a completely different Bruckner, you should look at the concert recordings from the 3rd to 9th. by Sergiu Celibidache with the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra: a Zen version, so to speak, broad tempos and deep immersion in Bruckner’s sound worlds including all the details. Great sound and mysticism.

Günter Wand also made a recommendable complete recording with the Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra. And then there is a complete recording that may seem bizarre at first, but certainly provides exciting insights: Hansjörg Albrecht recorded Bruckner’s symphonies in organ transcriptions.

In addition, there are many wonderful historical recordings of individual symphonies, some with limited sound, but sensational interpretations: Otto Klemperer with the Philharmonia Orchestra and the Fourth (the final movement!); the Seventh by Oskar Fried with the band of the Berlin State Opera in 1927 or Jascha Horenstein with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1928; Karajan’s late recordings of the Seventh and Eighth with the Vienna Philharmonic; Furtwängler’s Eighth with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra from October 1944 or Wand’s Ninth with the SWR Orchestra in 1979 from the Ottobeuren Basilica.

And Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s recordings of the Fifth and Ninth with the Vienna Philharmonic are highly recommended, especially since he recorded the missing fourth movement of the Ninth for the first time using the existing fragments – “Why did people actually think for 100 years that there was nothing of this fourth movement ?”

There is a birthday playlist on Spotify, compiled by the author here

Subscribe to the “nd”

Being left is complicated.

We keep track!

With our digital promotional subscription you can read all issues of »nd« digitally (nd.App or nd.Epaper) for little money at home or on the go.

Subscribe now!

sbobet88 sbobet88 demo slot x500 sbobetsbobet88judi bola